Music From Movies

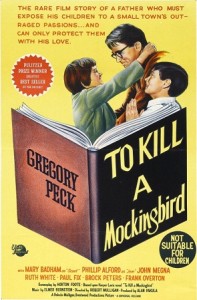

En route to a communications degree at Texas A & M University, I was required to take two semesters of film history. A month or so into the first semester film class, Dr. Bill Huie, the professor, brought in an old reel-to-reel of a lecture made by composer and conductor Elmer Bernstein, who had written scores for films like The Magnificent Seven, The Man with the Golden Arm and Some Came Running. The Bernstein lecture had taken place shortly after Robert Mulligan’s To Kill a Mockingbird had been released into theaters. Dr. Huie was at the lecture, and the astute observation he made that day was recorded for posterity and for many impressed students before and after me.

With a sheepish grin, Dr. Huie shut the reel-to-reel off and gave us the identity of the enthusiastic, observant student on the recording. He went on to discuss further the connection between the film score and the children in To Kill a Mockingbird and that of film and music over all. That day changed the way I watched film as I began to listen for the music as well. Perhaps if I had been more familiar with Wagner and “leitmotif,” the concept of To Kill a Mockingbird’s music representing the film’s children might not have had the profound effect that it did.

The marriage between music and film goes back before talkies when Shostakovich accompanied silent films in the days of his youth trying to support himself through music school. Occasionally, Shostakovich outraged the audience with ironic improvisations. He would later write some film music of his own. Camille Saint-Saëns is credited as having been the first classical composer to write film music. In 1908 he wrote the music for L’Assassinat du Duc de Guise, a film about Henry III. And in spite of Charlie Chaplin’s reservations about sound in film, he still produced some of his own music for City Lights, Modern Times and Limelight. Though a great cinematic partner, film music can and has enjoyed its own autonomy and limelight. Before the age of video tape and DVD’s, people bought soundtrack recordings in droves. Like opera, if not more so, film music can be enjoyed without the nature of visual expectations or suggestions.

What is film music but music from movies! Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings is almost a mourning anthem in its association with films like Platoon and The Elephant Man. Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 became a 20th century sensation after the release of Elvira Madigan a 1960’s cult classic. Could the infamously famous love scene in Louis Malle’s second feature film Les Amants (The Lovers) have been as intensely passionate without the Brahms String Sextet in B-flat major, which will be forever associated with Jeanne Moreau’s unflinchingly honest performance? Excalibur was one of the 18 most popular films of 1981 due in part to its own holy grail, the evocative soundtrack. “Siegfried’s Funeral March” from Wagner’s Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods) and Carl Orff’s “O Fortuna” from Carmina Burana were the perfect accompaniment even though the timeline for the music and the story were at odds. Schubert’s Piano Trio in E flat has made the cinematic rounds as one of the major themes in Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 period piece Barry Lyndon as well as in Tony Scott’s 1983 horror classic The Hunger.

There are in fact some directors who prefer to use music that has already been written instead of composing a whole new score. Stanley Kubrick was notorious for scrapping a newly composed score for the original music, as he did most notably in 2001: A Space Odyssey, along with A Clockwork Orange, The Shining and Barry Lyndon. Not all but some directors will initially use a piece of music like “On the Beautiful Blue Danube Waltz” called “temp” or temporary music to edit a film. The director will have a composer write something along the lines of temp music to use in the finished product as was the case with Ken Russell’s 1980 Film Altered States. Using Béla Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin as the temp music, Russell had composer John Corigliano write music that delivered the same kind of driving rhythm as the Bartók.

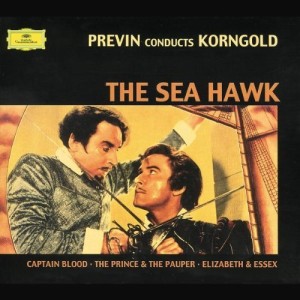

Years after learning to appreciate film music, I still qualified composers as film music composers or classical music composers. The distinction between what is and is not classical music can be blurred at times; however, there are composers who wrote for film who were and are perfectly legitimate classical music composers. Sergei Porkofiev, George Gershwin, Dmitri Shostakovich, Camille Saint-Saëns, Aaron Copland, Darius Milhaud, Leonard Bernstein, Elmer Bernstein, Nino Rota, Miklós Rózsa, John Williams, George De La Rue, Jerome Moross, Philip Glass, Ennio Morricone, Virgil Thomson, James Horner and Bernard Herrmann are but a few. Aside from Max Steiner, known as “the father of film music,” one of the greatest examples of a true blue classical composer associated with film was Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Korngold was a wunderkind who Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss enthusiastically championed. At thirteen Korngold premiered a two act ballet pantomime called The Snowman. He went on to become one of the founders of film music creating a familiar Hollywood sound emulated by countless others. The Adventures of Robin Hood, The Prince and the Pauper, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex and The Sea Hawk only scratch the surface of his compositional output for film. The composers of the 20th and 21st centuries are in some ways as busy as men like Bach and Handel who had to work hard and write a lot of music. As a rule people tend to flock to movie theaters more regularly than to music venues and concerts, so the big screen is a propitious means of presenting music even if it is in the background. In fact the big screen has made its way into the concert hall more and more. What a thrill to watch the Hitchcock horror classic, Psycho, fearlessly accompanied by the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. And most recently, the BSO played Prokofiev’s music with the Eisenstein film, Alexander Nevsky.

Film music is no longer only being played in a pops setting as there seems to be a growing trend towards classical musicians playing on film soundtracks or recording music from movies. Violinist Itzhak Perlman’s moving performance on John William’s Schindler’s List will remain memorable. Violinist Joshua Bell played John Corigliano’s score to the Red Violin and Iris by James Horner. Cellist Yo Yo Ma has released a couple of recordings paying homage to composers like Ennio Morricone featuring music from Spaghetti Westerns like The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West. Conductor Ricardo Muti recorded a number of suites from film scores written by his teacher Nino Rota –The Godfather, The Leopard, La Dolce Vita and La Strada.

Spanish film director Luis Buñuel said, “Personally I don’t like film music. It seems to me that it is a false element, a sort of trick, except of course in certain cases.” There have been film directors like Buñuel who for the most part did not like using a music score believing it was a distraction. If there were music at all it would be happening in the foreground not in the background of the film. The actual film score was represented by natural sounds and noise. Even then, I still listen for the music.

Did either Strauss dream of outer space?