Harry Smith and the Music that Changed the World

Harry Smith is not even mentioned in the Grove Dictionary of Music, but he may have been the biggest influence on popular music of the past half century. And he was not even a musician.

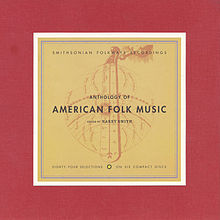

A true eccentric, Smith was a resident of New York’s Greenwich Village for most of his life. He was an artist, an experimental filmmaker, an occultist, an anthropologist, and a bohemian, as well as a mooch, who often asked his friends for food and money, then stayed to sleep on their couch. It is said that he was the first person to turn poet Allen Ginsberg on to marijuana. But his greatest claim to fame was a six LP collection that he compiled entitled Anthology of American Folk Music. Released in 1952 by Folkways Records, the album (sometimes simply called the Harry Smith Anthology) was the result of Smith’s obsessive collecting of 78 RPM records of American folk singers from the early days of commercial recording (circa 1927 to 1933). It is regarded as the recording that sparked the folk and blues revival of the 1960’s, which transformed international popular music to the present day.

The first records released a century ago were classical music. Tenor Enrico Caruso was the first million selling artist. But very quickly record companies learned that American popular song was an even bigger market. In 1917, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (an all white New Orleans ensemble) made the first jazz recordings. Then in 1920, blues singer Mamie Smith recorded “Crazy Blues”, the first blues recording in history. Like most of America, record executives had little regard for jazz or blues, but they recognized the possible profits from what today is known as “niche marketing”. Much to their amazement, “Crazy Blues” sold a million copies in less than a year, and talent scouts were sent around the country looking for more blues singers. These early recordings featured what is sometimes called “classic blues” or “vaudeville blues”, a female singer performing with a jazz band, a far cry from the electric blues bands of today.

As the decade wore on, however, niche marketing expanded to the Southern rural areas of America. Blind Lemon Jefferson made the first “country blues” recording, “Black Snake Moan”, in 1927. It was what a blues-loving friend of mine once called “the man with a guitar”, an iconic image which to many is the true “classic blues”. That same year, the Carter Family, followed within months by singer and guitarist Jimmie Rodgers known as “The Blue Yodeler”, made their first recordings for the Victor company, and became America’s first country music stars. Their songs, such as the Carter’s “Wildwood Flower” and “Will the Circle be Unbroken”, or Rodgers’ “T for Texas” and “Waiting for a Train” remain country standards to this day (although contemporary performances usually cut Rodgers’ yodel).

Thousands of other blues and country artists followed. For many of these recording sessions, record companies sent producers around the country with portable recording equipment, asking around rural communities for the best musicians in town. Some of them came straight from working in the coal mine or cotton field, and saw this as a chance at a new life. A few found success, at least locally, while others returned to their manual labor jobs. Many artists who would otherwise have been forgotten had their talent preserved on these early recordings. The Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers were exceptions, however. Particularly in the case of the blues, there was no attempt to mass market this music. It was thought to be of interest only to rural communities in the south.

The Great Depression brought an end to this early recording boom in 1933, and most of these artists were forgotten. Records were stockpiled in warehouses waiting to be destroyed. This was the world Harry Smith inhabited when he discovered the music and got the collecting bug. Going around not only to warehouses but door to door in black neighborhoods, Smith gradually amassed an enormous collection of the first commercial recordings ever made of American folk music. Even as a collector, Smith was a mooch. Recordings on the Anthology were never legally licensed from the recording companies that still owned them, at least not until it was reissued on CD in 1997. In all fairness to Smith, however, in 1952 there was no legal precedent for reissuing quarter of a century old recordings of dated ethnic music that the record companies had essentially thrown in the trash. Almost no original masters existed, so Smith not only preserved these recordings, but created a new market for them.

Before the 1950’s, country music was known as “hillbilly music”, and blues, by the late 1940’s rhythm and blues, was called “race music” by record companies, but Smith cannily ignored racial distinctions in packaging his Anthology. The six LP’s were divided into three double albums, titled “Ballads”, “Social Music” and “Songs”, and country and blues songs appeared side by side. Many have detected thematic connections in the sequencing of the songs, both in musical style and lyrics. The “Ballads” album contains many dark songs of jealousy, murder, and suicide, while counterculture historian Greil Marcus claims that the final song on the third album (“Fishing Blues” by Henry Thomas, one of the oldest performers on the Anthology) reveals the answer to the meaning of life is very simple: “Any fish bites if you got good bait”.

By the time Smith released the Anthology in 1952, much American folk music had had its rough edges smoothed off. Hearing these voices from a faded American culture proved revelatory for a new generation. Raspy, husky, twangy voices almost painful to the ear sang with thick regional accents from early in the century. Long assimilated by the 1950’s into a more homogeneous American dialect through the influence of radio and television, these old time singers’ lyrics are often incomprehensible to a modern listener without a dozen hearings or more. Folk musicians like Pete Seeger, John Fahey, and Bob Dylan recognized it as a lost American art form and helped spur its revival. I remember the first time I heard Bob Dylan’s voice in my teens I thought it was terrible. He was reviving the style of long forgotten singers like Buell Kazee, Dock Boggs, and Charlie Patton. Indeed, some have referred to the Anthology as “the secret history of rock and roll”. Rock singers whose appeal to teens in the 1960’s befuddled our parents had their roots in hillbilly and race music of the 1920’s.

Among the treasures of the Anthology are the first recordings of Louisiana Cajun music which were made by the Breaux Freres, a style that would reach the pop charts in the 1970’s in the recordings of Leon Russell and Doctor John. After Gus Cannon and his Memphis-based jug band Cannon’s Jug Stompers’ appeared on the Anthology, many of their other songs were reissued. “Walk Right In”, recorded in 1930, would reach number one on the pop charts in a cover version by the Rooftop Singers in 1962 (happily, Cannon was still alive to see it), and Cannon’s “Minglewood Blues”, an Anthology entry (along with “Big Railroad Blues” and “Viola Lee Blues”, not on the Anthology but released later) would all be covered by the Grateful Dead.

Among the treasures of the Anthology are the first recordings of Louisiana Cajun music which were made by the Breaux Freres, a style that would reach the pop charts in the 1970’s in the recordings of Leon Russell and Doctor John. After Gus Cannon and his Memphis-based jug band Cannon’s Jug Stompers’ appeared on the Anthology, many of their other songs were reissued. “Walk Right In”, recorded in 1930, would reach number one on the pop charts in a cover version by the Rooftop Singers in 1962 (happily, Cannon was still alive to see it), and Cannon’s “Minglewood Blues”, an Anthology entry (along with “Big Railroad Blues” and “Viola Lee Blues”, not on the Anthology but released later) would all be covered by the Grateful Dead.

I discovered the Anthology in 1997 when it was reissued on CD. I was teaching a high school course in American music at the time, and I found it enlightening. Prior to then, I had no knowledge of the earliest known recordings of American country music and blues. Indeed, I would have called the country recordings on the Anthology bluegrass, although they predate the first bluegrass recordings by over a decade. Some refer to this as Old-timey music, and these days the catchall term is “roots music”, but suffice it to say that guitar, banjo, even washboards, and twangy nasal singing are all in evidence, long before Bill Monroe refined the style into bluegrass in the 1940’s.

During my first listening, the songs grew on me gradually. Chubby Parker’s witty “King Kong Kitchie Kitchie Ki-Me-O” on the first disc (better known these days as “Froggie Went a Courting”) was the first to thoroughly charm me (“Way down yonder in a hollow tree. An owl, and a bat, and a bumblebee” Really!!). But by the time I got to disc four, I understood what one admirer meant when he said, “If God were a disc jockey, he would program like Harry Smith: “Dry Bones” by Bascom Lamar Lunsford, “John the Revelator” by Blind Willie Johnson, and “Little Moses” by the Carter Family.”

During the early days of its release, many fans of the Anthology referred to the second double album, “Social Music” as “the bad one”, probably because much of it is religious music. In my usual contrarion fashion, I will say that it is my favorite of the entire Anthology, especially the aforementioned disc four, which may be my favorite record of all time. Starting with a series of gospel choirs, and even an entire song by two unaccompanied female singers rasping in unison at full volume, “Better get ready for Judgement” (one sounds like a little girl having a tantrum, the other like somebody’s bossy mother-in-law who must be obeyed), the singers break all the rules of proper singing. Indeed, after years of choral directors telling me to stop singing so loud during my younger chorister days, and learning how to modulate my head voice and my chest voice to blend in better with an ensemble, these rural choruses from the 1920’s are vindicating. No one is trying to blend. It’s like the entire congregation letting it rip.

The three aforementioned “God’s disc jockey” songs that are perfectly placed near the end of the disc are as different as night and day. Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s “Dry Bones” is a white country gospel song accompanied by the singer on banjo. Various Biblical episodes are followed by the uplifting chorus, “I saw, I saw the light from heaven shining all around. I saw the light come shining. I saw the light come down.” In the final verse, the song has the audacity to rewrite the story of Adam and Eve: “Adam and Eve in the garden under that sycamore tree. Eve said to Adam, ‘You know Satan never tempted me’.” A sycamore tree instead of an apple tree, and Satan nowhere to be found, followed by the “saw the light” chorus, indicating the first Biblical couple found salvation post-Genesis through Jesus. Think about it. It’s brilliant.

Blind Willie Johnson did not like being called a blues singer. He sang gospel, and was also a preacher, but no one hearing his recordings today would call his music anything but the blues. Singing and accompanying himself on guitar in a proto rock and roll rhythm, Johnson’ s voice is awesome. Words like hoarse and gruff do not do it justice. It is a triple fortissimo baritone growl. “John the Revelator” refers to St. John who wrote the book of Revelations. Starting with the chorus, Blind Willie sings “Who’s that writing?”. A haunting soprano voice answers from a middle distance, “John the Revelator.” Three times through this call and response concludes with Blind Willie singing “Wrote the Book of the Seven Seals.” What a splendid, spooky effect is achieved juxtaposing the male and female voices (the latter quite lyric for once). Remember this was achieved with a single microphone in one take in the days before any processing equipment had been invented.

Months later, when I had bought the complete recordings of Blind Willie Johnson, I noticed the name of a different female singer credited on the song than the one cited on the Anthology. Looking into Blind Willie’s biography, however, I found the answer. Apparently he always sang with his wife, but Blind Willie was a bigamist, so no one is exactly sure which wife was singing with him at this session.

And that leads us to “Little Moses” by the Carter Family, the story of Moses being found in the bullrushes by Pharoah’s daughter. The legendary Sara Carter sings, “His mother so good did all that she could to rear him and teach him with care”. Moses in his infancy was, after all, no different from a rural American child with an upstanding mother who sees to it that he is given a proper Christian upbringing. I love the line, “She called him her own, her beautiful son. And she sent for a nurse who was near.” Pharoah class priveleges were not lost on the Carters. It’s an appropriately upbeat conclusion to this amazing tryptich.

In 1991, Harry Smith received a Chairman’s Merit Award at the Grammy Awards ceremony for his contribution to American Folk Music. He told those gathered there, “I’m glad to say my dreams came true. I saw America changed by music.” Later that year, Harry Smith would die at the Chelsea Hotel in New York.

Henry Thomas-Fishing Blues http://www.youtube.com/embed/zo-VUL6V4EQ

Cannon’s Jug Stompers-Minglewood Blues http://www.youtube.com/embed/lxR8myBIDds

Chubby Parker-King Kong Kitchie Kitchie Ki-Me-O https://www.youtube.com/embed/9piXcC7o_qk

Rev. Sister Mary Nelson-Judgement http://www.youtube.com/embed/7pJz323LG8w

Bascom Lamar Lunsford-Dry Bones http://www.youtube.com/embed/sLAavP5DPeU

Blind Willie Johnson-John The Revelator http://www.youtube.com/embed/5hucTDV1Fvo

The Carter Family-Little Moses http://www.youtube.com/embed/9IFZVfulj-0

Tags:American eccentric, blues, country music, early recordings, ethnomusicology, folk music revival, roots of rock

3 Responses to Harry Smith and the Music that Changed the World