Art Heals

By Judith Krummeck | Posted in Host Blogs | Comments Off on Art Heals

At 10:45 am on Friday, August 12th, we were in the amphitheater at the Chautauqua Institution in Western New York eager for Salman Rushdie to appear on stage. One of the many privileges I will never take for granted about living in America is the access we are able to have to people of his stature. When he walked out onto the platform, the 2,000+ audience members erupted into applause, which he acknowledged with a smile and nod before he took his seat.

As the Director of the Literary Arts at the Chautauqua Institute began introducing Rushdie from the podium, my eye was caught by a man jumping up onto the stage. Within a second he was on Rushdie, pounding him with stabbing motions. Rushdie rose quickly from his chair and stepped away to his left. He showed such dignity and courage, not fleeing, just keeping his eyes pinned on his attacker, alert. The man lunged at him, knocking him to the ground, repeatedly stabbing him before swiftly responding audience members were able to drag the attacker away and pin him down.

In twenty seconds, the world changed in front of our eyes. From elation to horror; from anticipation to disbelief.

Yet, when we congregated at the amphitheater again on Saturday evening to see the Washington Ballet dance works choreographed by Balanchine to music by Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky, we experienced—as so many millions have before—how art can heal. This is not to say that those twenty seconds will ever stop playing and replaying in my mind’s eye, but art can help to ameliorate horror. And so, though the final class of my five-part series, Synergy of the Arts Across Ages, was canceled along with all the others on that Friday afternoon, I want to share with you some of the highlights from the course, as I had promised to do.

I wrote HERE about the way that art forms—poetry, music, dance, design—came together in The Afternoon of the Faun. That concept was the basis of my course at Chautauqua, looking at ways in which the arts interact with each other to create the specific ethos of an age, whether that be Classical, Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, Neoclassical, Romantic, or Post Romantic.

Homer’s epics The Iliad and The Odyssey; the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes; our country’s democracy; and the architecture of our nation’s capital all reflect back to CLASSICAL Greece, and we need only pay a visit to the Walters Art Museum to see their fine collection of classical sculpture.

Sadly, painting and music have proved more ephemeral over time, and we don’t have as clear a link to those art forms. But fragments of musical scores and remnants of instruments survive, and musicologists have been able to reconstruct from literary and artistic references some sense of how music was practiced. All poetry, epics, and drama were sung, and instruments that were plucked, blown, or beaten were an integral part of marriages, funerals, religious ceremonies, even war.

One of the many intriguing aspects about the distinct artistic eras over the centuries is the pendulum swing of Position and Opposition, by which I mean the way that one era frequently pushed back against its predecessor—like a teenager rebelling against her parents. The ideals from the Golden Age of Greek antiquity had lost their way after the fall of Rome and during the Medieval era. Then, in the 14th and 15th centuries, scholars and thinkers began to study ancient Greek thought and philosophy in translation. The resulting RENAISSANCE restored a spirit of classicism that was in opposition to the shadowy afterlife and self-abnegation of the Medieval era.

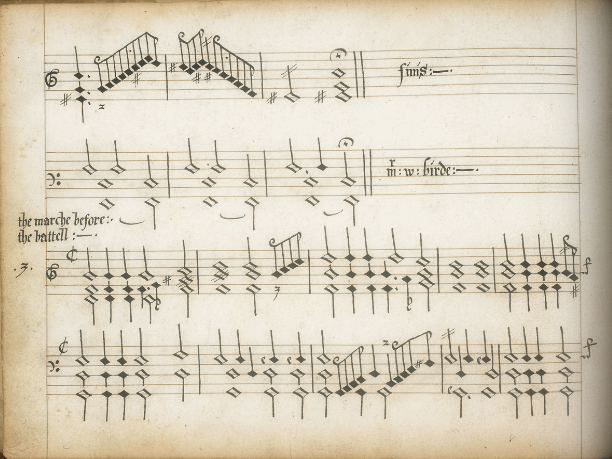

Our Modern world has its beginnings in the Renaissance, flourishing first in Florence under the patronage of wealthy families like the de Medicis, with powerhouse visual artists like Botticelli, da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. The architecture turned away from the soaring arches of the Gothic cathedrals to the form and structure of ancient Greek and Roman temples and basilicas. It was the time of writers like Petrarch, Cervantes, and Shakespeare, and of musicians like William Byrd, John Dowland, and Thomas Tallis.

Manuscript page of William Byrd extract to

My Ladye Nevells Booke, The marche before the battell

Handwritten by the calligrapher John Baldwin

(before 1560–1615)

British Library MS Mus. 1591

Although music notation had its early roots in the Medieval era, when Guido of Arezzo invented (or some say developed) four-line staff notation, the system of notation evolved during the Renaissance to include staffs indicating pitch, notes designating time, and bars denoting meter. While church music still formed a major part of the musical output, songs and dances were steadily growing in popularity. And, although vocal music continued to predominate, some purely instrumental arrangements were starting to become more common.

It was during the BAROQUE era that instrumental music truly came into its own. “Baroque” was initially a pejorative term, derived from the French, Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian words for an irregularly shaped pearl. Here again, the movement was a pushback against its predecessor. Where the Renaissance was all about harmony and proportion, the new era was one of decorations, perspective effects, and bold and virtuosic formal solutions.

The Italian dancer-composer Jean-Baptiste Lully introduced opera to the French court at Versailles, and he is also credited with the French overture—a short, two-part composition used to introduce a vocal or instrumental work—which developed ultimately into the symphony. But it is the Baroque giants, Antonio Vivaldi, George Frederick Handel, and Johann Sebastian Bach to whom we have the greatest debt for catapulting the musical language forward during the Baroque era. Vivaldi left us an astonishing circa 500 concerti. Handel, in a style that was richly ornate, lively, full of beautiful melodies, pomp, and dramatic climaxes, wrote over 40 operas, over 30 oratorios, and instrumental music that includes the staple Water Music and Royal Fireworks. Bach, less celebrated than Handel during his lifetime, composed a vast body of contrapuntal music, weaving together two or more independent but harmonically related melodic parts in a way that would have been unimaginable in previous eras.

Composers like Bach’s youngest son, Johann Christian, writing in a lighter, more delicate Galant style, formed the bridge to the next era: NEOCLASSICISM. In yet another pushback, the ethos of this age was an attempt to recover the classical ideals of form, balance, and reason in literary, visual, and musical arts, while architecture—especially popular in the young republic of the United States—borrowed from antiquity even more faithfully than it had during the Renaissance.

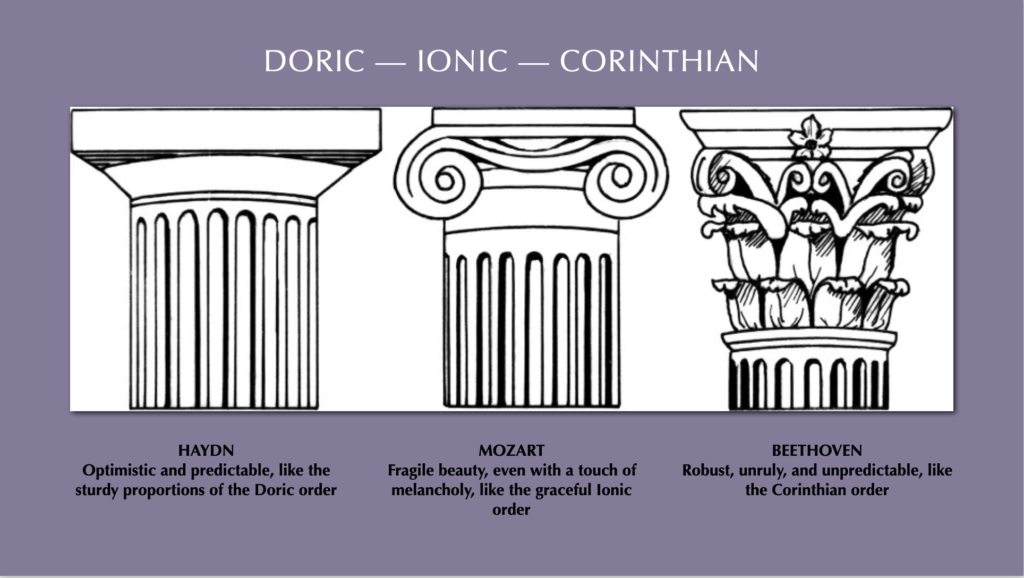

Two hugely important musical developments evolved during this era: sonata form and the symphony, meaning “sounding together.” Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, the three geniuses who brilliantly utilized, developed, and expanded on these forms, make me think—rather fancifully, perhaps—of the three orders of the ancient Classical era.

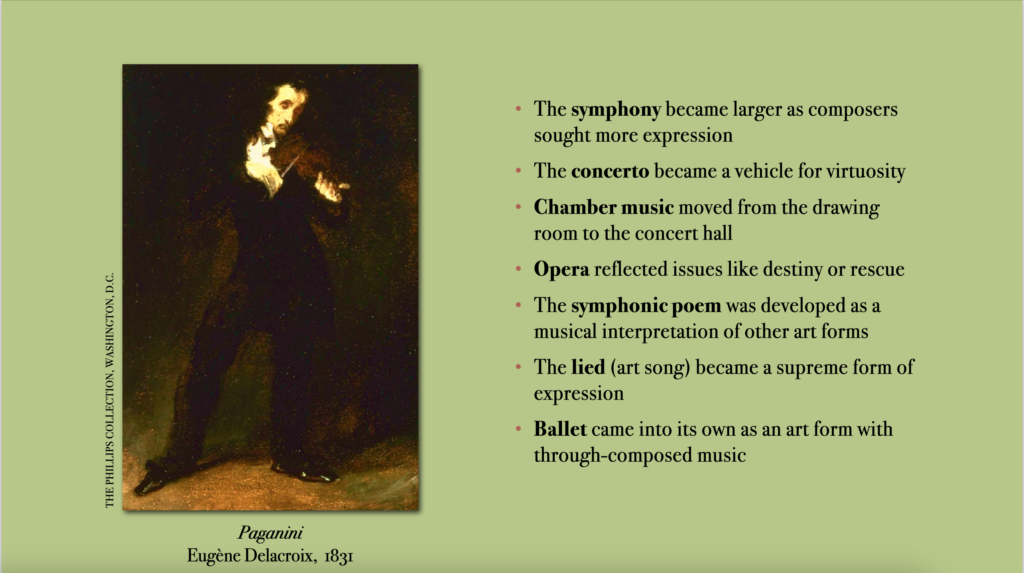

Beethoven is the link to ROMANTICISM, an age defined by self-expression. For classical composers, form and order were the most important aspects. For the Romantics, expressive content was their most important consideration, with form being the means to that end. In literary, visual, and musical arts, the defining elements of the Romantic age were exotic places, romantic love, the beauty and violence of nature, and the Medieval lure of the supernatural and the strange.

From Schubert—who is sometimes referred to as the 4th great “Viennese Classicist,” after Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven—through the Mendelssohns and the Schumanns, to composers as diverse as Chopin, Liszt, Verdi, and Brahms, music was no longer a servant of the Church or an ornament of the rich but a fundamental part of civilization itself, with virtuosic musicians perceived as the Artist as Hero.

There is no clear demarcation of the end of Romanticism in music. Some musicologists date it to the Post-Wagnerian period, others to the crucial years before the outbreak of the First World War. Had Brahms not died in 1897 at the relatively young age of 63, he would have lived into the 20th century. Mahler, Richard Strauss, Sibelius, and Elgar all composed into the 1900s, while Rachmaninov wrote in a Romantic style into the 1940s. Even today, in some film scores, you can hear echoes of Rachmaninov or Mahler.

If the 18th-century Neoclassical era was a return to form and balance after the florid lines of the Baroque, and Romanticism was a reaction of feeling against the rules of reason of Neoclassicism, POST-ROMANTICISM was a response to the fervid imagination of the previous era. The colors and paint techniques of Turner, Constable, and Delacroix evolved into Impressionism, Expressionism, and Abstract Art. William Wordsworth’s “language really used by men” found an outlet in novels like Flaubert’s Madame Bovary and Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, as well as the Realism of plays like Henrick Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler and Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya—which led ultimately to the ultra-realism of method acting and film. In music, Wagner’s chromaticism was pushed to the extremes of the 12-tone system of Schönberg and his disciples, and the minimalism of Henryk Górecki or Arvo Pärt.

The closer we get to our own time, the more difficult I find it to take an objective overview. Often, our era seems to be made up of myriad strands that might or might not cohere. But, if I trace the arc back to the ancient Greeks and put artistic movements in the context of Position and Opposition, it helps to make some sense of our current era—even if senseless violence might try to rob us of it.

Wishing Sir Salmon Rushdie the best possible recovery!

Tags:WBJC newsletter