The Many Faces of the Faun

The Many Faces of the Faun

As I was wandering around the media preview of A Modern Influence: Henri Matisse, Etta Cone, and Baltimore, which is on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art until January 2nd, it struck me once again how magical it is when the arts collide. My little epiphany happened in the gallery displaying some of Etta Cone’s most important purchases, the maquette, or preliminary drawings, for the first of Matisse’s thirty-eight artist’s books, Poésies de Stéphane Mallarmé. In particular, it was Matisse’s illustrations for the poem, L’après-midi d’un faune, or The Afternoon of a Faun.

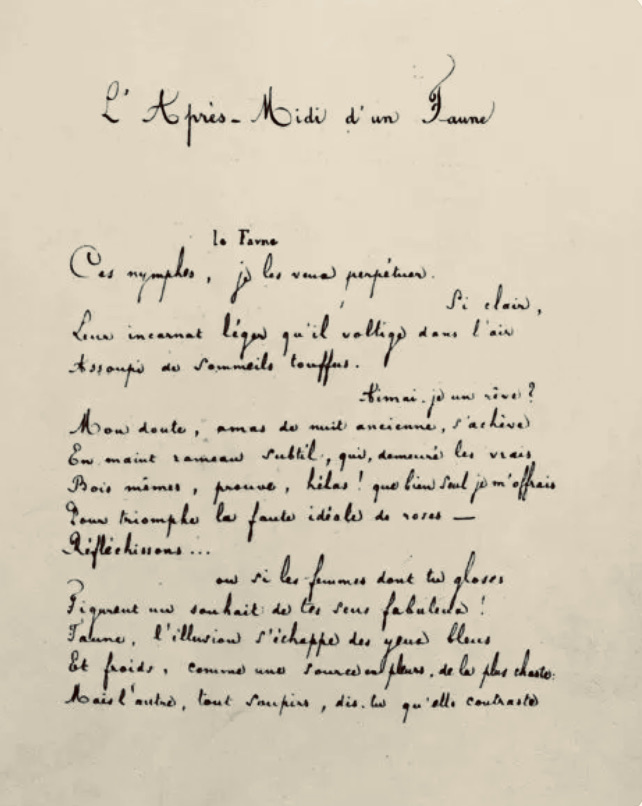

Manuscript of “L’après-midi d’un faune”

by Stéphane Mallarmé

The French poet, Stéphane Mallarmé, along with compatriot Paul Verlaine, developed a Symbolist aesthetic in the 1860s and 1870s as a reaction against the movements of Realism and Naturalism. Mallarmé maintained that “to name is to destroy; to suggest is to create,” and the Symbolists’ aim was to use metaphorical imagery to allude to truths. Mallarmé’s best known poem, L’après-midi d’un faune, draws on the Greek myth of the faun Pan, half man-half goat, who pursues the nymph Syrinx. In Mallarmé’s sensual poem—produced in 1876 with several illustrations by Édouard Manet, after having been rejected by several other publishers—the faun has just woken from an afternoon nap on a sultry summer afternoon, and he muses about whether two beautiful nymphs are the remnants of a dream or if he caught a glimpse of them as he woke.

Mallarmé’s poem provided the inspiration for a number of musical works, amongst them Darius Milhaud’s Chansons bas de Stéphane Mallarmé (1917); Maurice Ravel’s Trois poèmes de Mallarmé (1913); and—most famously—Claude Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894). Debussy, who thoroughly disliked the term Impressionist as applied to his music, was inspired almost exclusively by texts and themes by Symbolist writers. Amongst these are art songs from poems by Paul Verlaine, and his opera, Pelléas et Mélisande, to a libretto by the Belgian playwright, Maurice Materlinck, whose plays provided an important contribution to Symbolism.

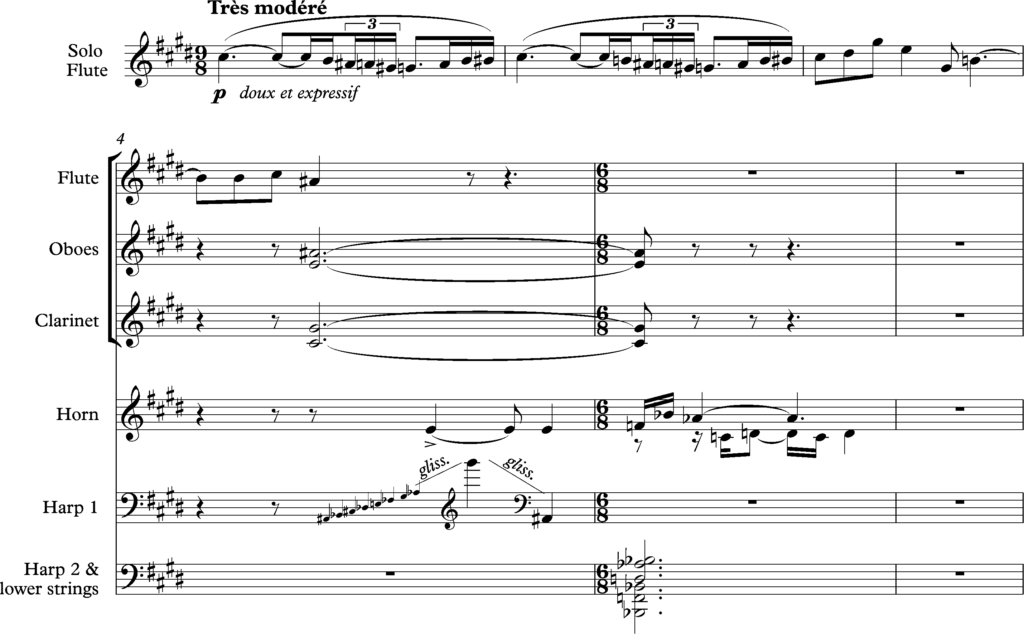

Debussy, “Prélude à l’après midi d’un faune,” opening bars

In describing Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, Debussy wrote: “The music of this prelude is a very free illustration of Mallarmé’s beautiful poem. By no means does it claim to be a synthesis of it. Rather there is a succession of scenes through which pass the desires and dreams of the faun in the heat of the afternoon. Then, tired of pursuing the timorous flight of nymphs and naiads, he succumbs to intoxicating sleep, in which he can finally realize his dreams of possession in universal Nature.” Pierre Boulez—whose composition for solo soprano and orchestra, Pli selon pli or Fold by fold, uses the poetry of Mallarmé—said of Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune that “the flute of the faun brought new breath to the art of music.”

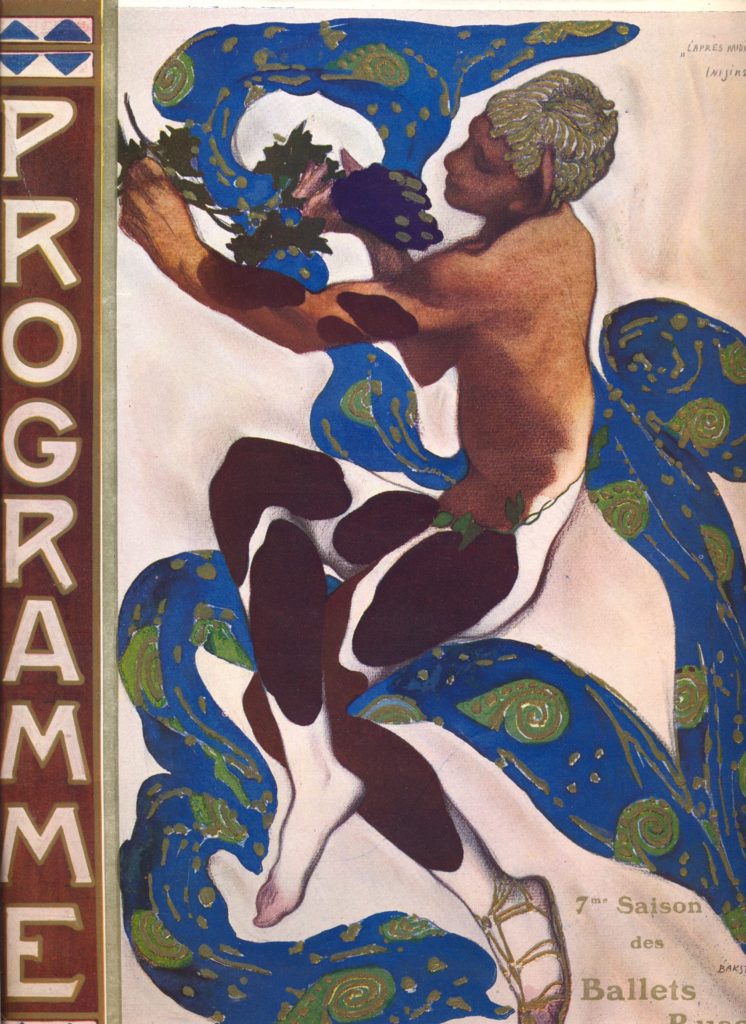

Leon Bakst: Vaslav Nijinsky in the ballet “L’après-midi d’un faune”

Debussy’s music, in turn, inspired ballets from such diverse choreographers as Russia’s Vaslav Nijinsky for the Ballets Russes in 1912 and America’s Jerome Robbins for New York City Ballet in 1953. L’après-midi d’un faune was the first ballet that Nijinsky made, and it was controversial on practically every level. To the consternation of the Parisian audiences, it broke away from classical ballet forms. Nijinsky and his designer, Léon Bakst, staged the ballet to conjure images on a Greek vase, so the dancers often moved across the stage in profile to suggest a two-dimensional painting. Also, the dancers were barefoot. Most controversial of all, the eroticism of the faun left little to the imagination.

Robbins’ choreography, by comparison, was relatively tame. He set his ballet in a dance studio, where a male dancer lounges on the floor. A ballerina comes in and they dance, facing the audience, as if watching themselves in the studio mirrors. He kisses her on the cheek, she bourrées out of the studio, and he goes back to lazing on the floor.

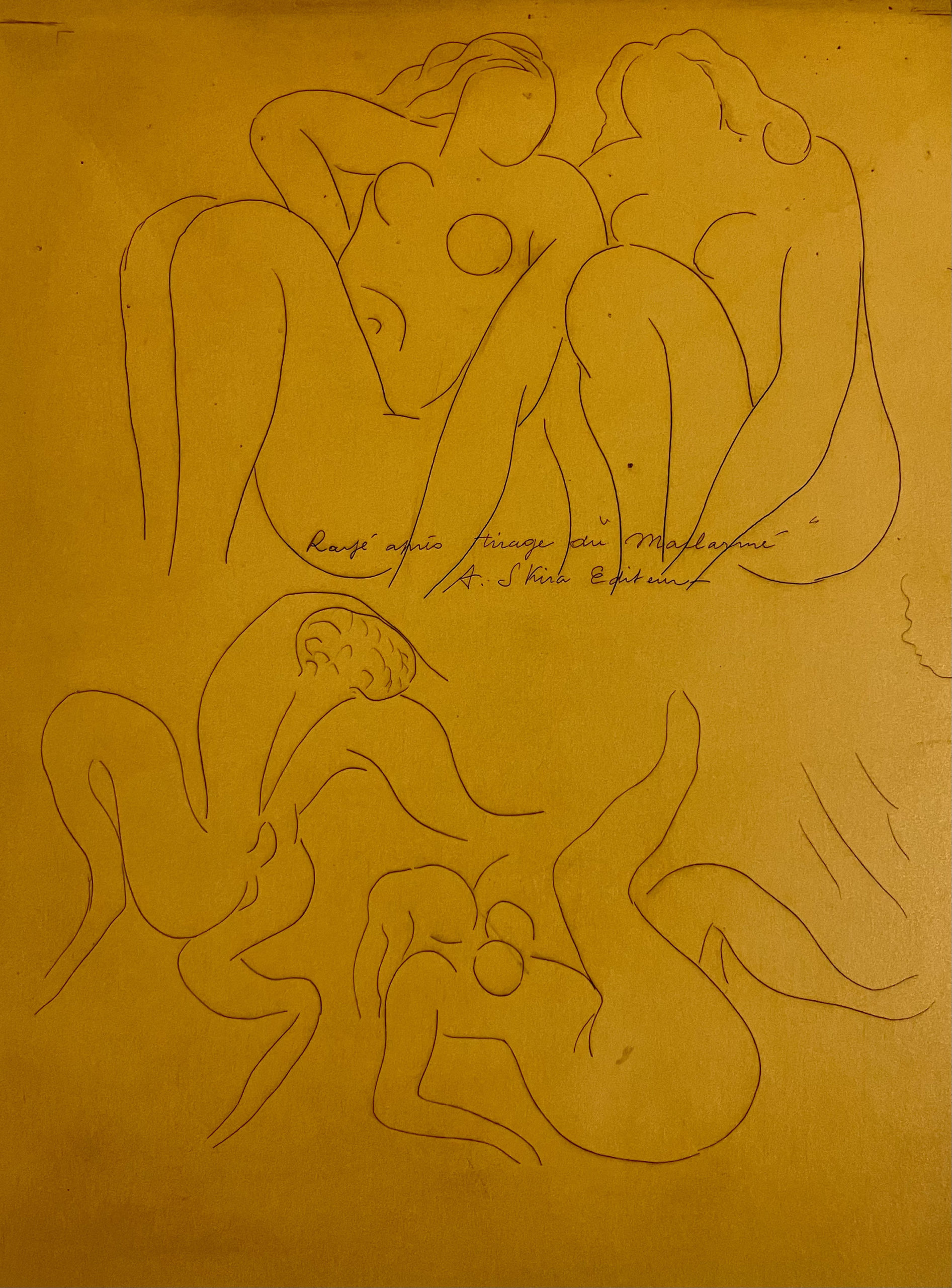

Matisse’s headpiece from “The Faun” (copper plate) 1932

Midway between these two dance interpretations of L’après-midi d’un faune comes Henri Matisse’s first artist’s book, Poésies de Stéphane Mallarmé or Poems of Stéphane Mallarmé, produced in 1932 by the Swiss publisher, Albert Skira. Included amongst other poems with titles like The Jinx, Summer Sadness, Herodias, The Flowers, The Swan, and The Hair, are five different illustrations for The Afternoon of a Faun—the most of any in the collection. In the maquette of Etta Cone’s collection, there are numerous studies, sketches, and etchings of the nymphs and of the faun, as well as Nymph and Faun, which is as explicitly sensual as Nijinsky’s ballet from twenty years earlier.

Matisse had designed sets and costumes for the Ballet Russes when they produced Igor Stravinsky’s The Song of the Nightingale in 1920, and it’s likely that he was aware of Nijinsky’s groundbreaking choreography for L’après-midi d’un faune. Yet, even without that possibility, there is this fascinating dialogue between the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé, the music of Claude Debussy, the dance of Vaslav Nijinsky, and the visual art of Henri Matisse.

Each iteration stands alone as a work of art, but taken together they demonstrate with resounding clarity a turning point in Western art.

Tags:The Afternoon of a Faun