One Hundred Years On

This year marks the 100th anniversary of women’s right to vote in America. The 19th Amendment to the constitution was passed by Congress on June 4, 1919, and ratified on August 18, 1920. It has to be said, though, that while black women were legally entitled to vote, they were effectively denied voting rights in many Southern states until 1965.

In my native country, although European and Asian women were allowed to vote in 1930, it wasn’t until South African independence in 1994 that women of other races, as well as men of all races, were enfranchised. In the United Kingdom, women could vote—at 30 years of age with property qualifications, or as graduates of UK universities—from the year 1918, while men could vote at 21 with no qualification. From 1928 British women had equal suffrage with men.

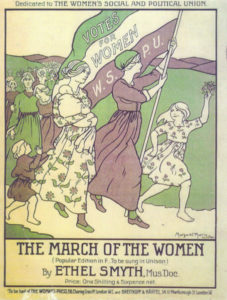

This is all very well, I hear you say, but what has it got to do with a classical music radio station? Well, Dame Ethel Smyth—whose compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works, and operas—was a member of the women’s suffrage movement in England, to the extent that she gave up music for two years to devote herself to the cause. She joined the suffrage organization, the Women’s Social and Political Union, in 1910, and the following year she composed The March of the Women, which became the anthem for the women’s suffrage movement.

This is all very well, I hear you say, but what has it got to do with a classical music radio station? Well, Dame Ethel Smyth—whose compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works, and operas—was a member of the women’s suffrage movement in England, to the extent that she gave up music for two years to devote herself to the cause. She joined the suffrage organization, the Women’s Social and Political Union, in 1910, and the following year she composed The March of the Women, which became the anthem for the women’s suffrage movement.

When the leader of the suffragists, Emmeline Pankhurst, called on members of the union to throw stones at the windows of houses belonging to politicians who opposed voting rights for women, Ethel Smyth was an enthusiastic participant, and was amongst the hundred women who were arrested. Smyth’s friend, the conductor Thomas Beecham, went to visit her in Holloway Prison, where he found the imprisoned suffragists marching and singing in the quadrangle while Ethel Smyth conducted with a toothbrush. In 1930, Smyth conducted the Metropolitan Police Band—this time with a baton—at the unveiling of the statue of Emmeline Pankhurst in London.

Ethel Mary Smyth was born the fourth of eight children on April 22nd 1858, though her family always celebrated her birthday on April 23rd to coincide with Shakespeare’s birth date. Her father, a major general in the Royal Artillery, was vehemently opposed to her studying music, but she prevailed, and she pursued her education at the Leipzig Conservatory, where she studied composition with Carl Reinecke. Although she left after a year, disillusioned by the standard of teaching, she stayed on in Leipzig to study privately, and she met Clara Schumann. (She also met Brahms, Dvořák, Grieg, and Tchaikovsky, but I like to think that they made less of an impression on her.)

Portrait of Dame Ethel Smyth, 1901, John Singer Sargent

Chalk on paper, National Portrait Gallery, London

Ethel Smyth struggled for recognition as a composer in a field dominated by men. Dr. Eugene Gates, a faculty member of the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, summed it up best in a 2006 article called, Damned If You Do and Damned If You Don’t: Sexual Aesthetics and the Music of Dame Ethel Smyth:

On the one hand, when she composed powerful, rhythmically vital music, it was said that her work lacked feminine charm; on the other, when she produced delicate, melodious compositions, she was accused of not measuring up to the artistic standards of her male colleagues.

Still, Smyth’s second opera, Der Wald, was produced at the Metropolitan Opera in 1903, and was for more than a century (until L’Amour de loin by Kaija Saariaho in 2016) the only opera by a woman composer produced at The Met. She was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1922, the first woman to be awarded a damehood in recognition of her work as a composer. In honor of her seventy-fifth birthday in 1934, her work was performed at the Royal Albert Hall, in the presence of Queen Mary, in a program conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham.

By the time of this music festival in her honor, Dame Ethel—like Beethoven and Smetana before her—was completely deaf. Undaunted, she found another outlet to add to her having been a composer and a suffragette, and she became a writer, going on to publish ten successful books before her death in 1944 at the age of 86.

I wish it could be said that Dame Ethel Smyth had been a trailblazer for the success of women composers, but their recognition continues to move at glacial speed. When Hildur Guðnadóttir won the Academy Award this year for her film score for Joker, she was only the fourth to do so, and the first since 1997.

So, in this milestone year for women, let’s give a shout out to just some of the other women composers who have helped to move the dial over the past 900+ years:

Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179)

Marianna Martines (1744-1812)

Fanny Mendelssohn (1805-1847)

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944)

Amy Beach (1867-1944)

Florence Price (1887-1953)

Germaine Tailleferre (1892-1983)

And living composers, Joan Tower, Thea Musgrave, Missy Mazzoli, Caroline Shaw, Libby Larsen, Rachel Portman, Sally Beamish … et al. Brava!

Tags:Dame Ethel Smyth

10 Responses to One Hundred Years On