A Panoply of Immigrant Composers

As the debate about immigrants continues in the headlines, and being an immigrant myself, I often find myself thinking about the ways that migrants have left their indelible marks on our country over the years and decades—Albert Einstein, Andrew Carnegie, and Joseph Pulitzer are just some who spring to mind. The number of immigrant musicians—ranging from Irving Berlin to Yo-Yo Ma—is countless, but I want to highlight here just seven naturalized American composers who had a significant impact on the music of this country.

We can’t really claim Antonín Dvořák as an immigrant because he was only here from 1892 to 1895, but he was so seminally important in exploring the roots of American music—his Symphony No. 9, From the New World, being the most radiant example—that I like to give him honorary status as an immigrant. Dvořák had been invited to America as an honored guest and teacher at the National Conservatory of Music in New York, but all of the immigrant composers I’m sampling here came to States as a result of strife or persecution in their native countries.

Sergei Rachmaninoff (U.S. citizen 1943)

Rachmaninoff with a piano score, digitaly restored by Etincelles, Public Domain.

Rachmaninov made his debut tour of America in 1909, giving 26 performances—19 as pianist and 7 as conductor. When he was trying to decide whether to leave Russia in the midst of the violent chaos of the 1917 Revolution, he was invited back to America to conduct the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the Boston Symphony, and to give twenty-five piano recitals—but he turned them down, unwilling to take on such extensive commitments so far away from Europe and Russia. Eventually, though, fiscal necessity overcame his scruples, and he set sail for America with his family in November 1918. He quickly established a financially rewarding touring and recording schedule. The Rachmaninovs lived first in New York, but he moved later to California for health reasons. Here, he befriended two musicians from the Russian Empire: Vladimir Horowitz, with whom he would play piano duets, and Igor Stravinsky, with whom he could commiserate about the poor state of things in their native country. Rachmaninov’s composing output slowed in his adopted country, in part because of his busy performing schedule, but also because, as he said, “I left behind my desire to compose: losing my country, I lost myself also.” He only completed six new compositions during his American years, the major ones being his Fourth Piano Concerto, the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini (premiered by him at the Lyric Opera House in Baltimore Maryland in 1934), and his Third Symphony. It is enough, though, to claim these works as ours.

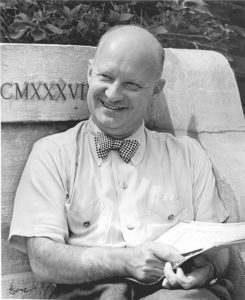

Igor Stravinsky (U.S. citizen 1945)

Igor Stravinsky, United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Although Stravinsky also left Russian as a result of the 1917 Revolution, he took longer to get here. After the success of The Firebird in Paris in 1910, he and his family spent the summers in Russia and their winters in Europe. Then, when the borders were closed during World War I, and the Russian Revolution broke out shortly thereafter, Stravinsky settled in Europe—first in Switzerland and later in France. It wasn’t until the outbreak of World War II in 1939 that he sailed for America. He settled in Hollywood and, although his last years were in New York, he ended up spending more of his life in Los Angeles than anywhere else in the world. He was drawn into the growing cultural circles there; he appeared on the cover of Time magazine; he has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame; he was given a posthumous Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement. As a composer, he was prolific in America—his earliest works here being his Concerto in E-flat Dumbarton Oaks and his Symphony in C. He brought with him the offbeat, compelling rhythmic drive that so defined works like The Rite of Spring, and it was this, perhaps most of all, that would come to influence American composers like Aaron Copland.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was just one of the chaotic world events that resulted in a diaspora of immigrants spreading out all over the globe. Similarly, the Nazi uprising was a catastrophic event that caused widespread displacement and upheaval, and all the remaining stories of the immigrant composers I’m highlighting were touched by this horror in some way.

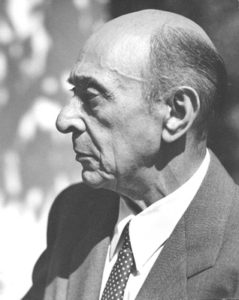

Arnold Schoenberg, Los Angeles, 1948, Schoenberg Archives at USC.

Arnold Schoenberg (U.S. citizen 1941)

Schoenberg was vacationing in France in 1933 when he received word that it would be dangerous for him to return to Germany. He had two “black marks” against him according to the Nazis: he was Jewish, and his atonal music was considered degenerate. He first tried to find asylum in Britain, but to no avail. In America, he found a teaching position in Boston before going on to the University of California in Los Angeles. It would seem that he was not a happy transplant, as least to begin with. In the 1930s, he explored the possibilities of relocating again—first to Australia and then to New Zealand—before he eventually became at United States citizen in 1941. Schoenberg could count amongst his friends George Gershwin (also his tennis partner), and he held Sunday afternoon gatherings at his Spanish Revival villa in Los Angeles, which were famous for their Viennese coffee and pastries. At UCLA, he was a hugely influential teacher—John Cage being one of his most renowned students—and even though tonality has found its way back into much of the new music of today, Schoenberg’s concepts of atonality, the 12-tone system, and serialism were dominant in America for a large part of the 20th century.

Kurt Weill and his wife, Lotte Lenya, 1942. By Wide World Photos.

Kurt Weill (U.S. citizen August 27, 1943)

The music of Kurt Weill arrived in America before he did. His musical collaboration with Bertold Brecht on The Threepenny Opera, including probably his most famous song, Mack the Knife, had its premiere on Broadway in April 1933. In March of that year, Weill, targeted by the Nazis as a Jew and a prominent German composer, had fled his native country, and touched down first in Paris and then London before arriving in New York in 1935. Intrigued by American popular and stage music, Weill made a study of it, and began to incorporate it into his own work, becoming one of the seminal composers of what we now think of as the American musical.

Photograph of Erich Wolfgang Korngold by Hermann Brühlmeyer from the Austrian National Library

Erich Korngold (U.S. citizen 1943)

Korngold was a prodigiously talented composer in Vienna—just 11 when his ballet, The Snowman, was produced—and he was a professor of music at the Vienna State Academy by his early 20s. In the face of Jewish persecution by the Nazi regime, Korngold decided to accept an invitation from the movie director, Max Reinhardt, to move to Hollywood in 1934 to write film scores. He was the first composer of international stature to write movie music, and he is one of the most important pioneers of writing music for film. He produced sixteen film scores—Captain Blood,The Adventures of Robin Hood, The Sea Hawk, and Elizabeth and Essex amongst them—and he won two Oscars, along with two more nominations. Although many (Korngold’s father amongst them) considered his talent wasted on film music, his lush, almost Richard Straussian melodies had an effect on the industry that still resonates today.

Béla Bartók (U.S. citizen 1945)

Pianist and composer Béla Bartók, before 1945, National Archive

Bartók was raised a Catholic, so it was not Jewish persecution that made him leave Hungary during World War II, but his strong opposition to his country’s alliance with Germany. His anti-fascist convictions made it increasingly untenable for him to remain in Hungary and, in 1940, having sent his manuscripts ahead, he sailed for America. He never felt fully at home in our country. He struggled financially and, although he was respected as a pianist, teacher, and ethnomusicologist, it was difficult for him to find a voice for his composing here. Towards the end of his life, though—cut short at the age of 64 by leukemia—a spurt of creative energy produced some of his great masterpieces. These included his Concerto for Orchestra, commissioned by Serge Koussevitsky for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and his Third Piano Concerto. The style of Bartók’s late period is known as “Synthesis of East and West,” and it seems to me that the term can also be applied to the idea of an immigrant trying to come to terms with the dislocation of having left their native country, adopting a new one, and the synthesis that must come about as a result.

Paul Hindemith during the 1940s, USA. Hindemith Foundation.

Paul Hindemith (U.S. citizen 1946)

Paul Hindemith, like the Russian composers under the post World War II Stalinist regime, had a troubled relationship with the Nazis. One the one hand, they labeled him an “atonal noisemaker” while, on the other hand, they thought he might be useful to tout as a modern German composer. The situation was complicated, too, by the fact that Hindemith’s wife was partially of Jewish ancestry. In the late 1930s, Hindemith toured America several times as a viola and viola d’amore soloist, and, in 1940 he settled in the United States, after two years of living in Switzerland. While he was teaching at Yale University, he founded the Yale Collegium Musicum. He also taught at the Universities of Buffalo and Cornell, and at Wells College, and he was invited to deliver a Charles Eliot Norton Lecture at Harvard. Amongst the compositions he wrote during his American years are the ballets, The Four Temperaments, choreographed by George Balanchine, and Hérodiade, choreographed by Martha Graham; the Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber; and a series of concerti for a range of instruments. Although Hindemith decided to return to Europe in 1953, he clearly left a mark on classical music in America during the thirteen years he spent here.

Every one of the stories of these seminal composers is shot through with that dilemma that any immigrant faces of having two (or more) countries but no home. In my book, Old New Worlds, which intertwines two immigrant stories, I recall how the judge who officiated at my citizenship ceremony enjoined us all never to lose the unique qualities we bring from our native countries, even as we became Americans. These immigrant composers did exactly that.

Tags:Immigrant composers

8 Responses to A Panoply of Immigrant Composers