Music in Art

Last July, I posted a piece with the subject heading, “The Impressionist Painter with a Flair for Music,” about the friendship between the French painter, Frédéric Bazille, and the musician and art patron, Edmond Maître, and how they bonded over their shared love of music.

Saint Cecilia, 1895, William John Waterhouse. “In a clear walled city on the sea. Near gilded organ pipes – slept St. Cecily” Legion of Honor, San Francisco.

Since then, I’ve been thinking quite a bit about music in art. There are, to begin with, countless images of St. Cecilia, the Patron Saint of Music, which date all the way back to Medieval times. This one by the Pre-Raphaelite, John William Waterhouse, is probably the most famous.

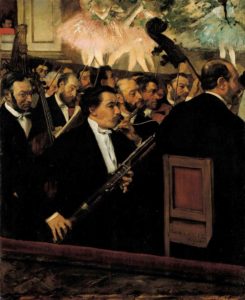

L’Orchestre de l’Opéra, Edgar Degas, 1870. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Another Impressionist image that jumped to mind was Edgar Degas’s musicians in the orchestra pit. (If that is the conductor sitting on the chair, then goodness knows what the bassoonist is doing in the 1st violinist’s place, but never mind!)

There’s Paul Gauguin’s portrait of the Swedish musician, Fritz Schneklund, 1894, at our own Baltimore Museum of Art. There’s Édouard Manet’s Spanish Singer, 1860, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. There’s the gloriously flamboyant Portuguese cellist, Guilhermina Suggia, by Augustus Hohn OM, 1920-3, at the Tate, London.

There are so many!

All this thinking crystallized beautifully when I went down to the National Gallery of Art again just before Thanksgiving to see the exhibition, Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry (on until January 21st, 2018), and I was struck by the number of his paintings that featured musical instruments and themes. When I looked into it further, I found some astonishing statistics: musical instruments are featured in some form or another in 14 of the 35 known paintings by Johannes Vermeer, and in 9 of his paintings music is a central theme. This is all the more remarkable because, to the best of our knowledge, Vermeer did not play a musical instrument (although his grandfather was a musician), and it is unlikely that he possessed any. The speculation is that he had access to them through some of his wealthy patrons.

The instruments that Vermeer chose to paint – virginals, a harpsichord, bass viols, citterns, lutes, a guitar, a trumpet, and a recorder – are interesting. Vermeer lived from 1632-1675, which would put him squarely in the Baroque era (Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck is probably the best known Dutch composer of the time), yet many of these instruments harken back to Renaissance times. This would also suggest that, for Vermeer, the instruments were objects of artistic interest rather than first hand experience.

In chronological order, then, here is a list of the 9 Vermeer paintings that have a musical theme. The ones in bold are the paintings that caught my attention in the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, and I’ll show them below. I invite you to seek out the others.

- Girl Interrupted at her Music

- The Music Lesson

- Woman with a Lute

- The Concert (stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, in 1990 and not recovered)

- The Girl with the Flute

- The Love Letter

- The Guitar Player

- Lady Standing at a Virginal

- Lady Seated at a Virginal

Music was evidently an integral part of Dutch life during the 17th century, notwithstanding the strict Calvinistic society – perhaps even because of it, in fact; it would have provided a welcome outlet. Add to this the fact that one of the unique features of Dutch genre painting – of which Vermeer was a master – was its interest in creating realistic scenes of everyday life, and music would have been a popular pastime of the haute bourgeoisie, whom Vermeer chose to represent.

Woman with a Lute, c. 1662–1665. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Certainly, the woman tuning the lute in this painting is is of that class. She wears an ermine-trimmed jacket and enormous pearl earrings (remember, The Girl with the Pearl Earring!) There is an air of the dilettante about her. Her distracted gaze out of the window might be that she is looking off into the middle distance as she focusses her ear on the sounding notes – but she might also be looking out expectantly for the person, presumably a man, who will come to pick up the barely discernible viola da gamba lying on the floor in the foreground, to join her in music making. This is the corner of a room that Vermeer loved. He painted it often – many times with the window open – and the light that spills in makes a gorgeous focal point for the diffuse tone that he creates. No reproduction can truly do it justice.

The Love Letter, c. 1667–1670. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The Love Letter, as its name implies, is only tangentially about music. It is much more about startled anticipation. But, for our purposes, it is interesting too, because the instrument she was playing before the maid brought the love letter is a cittern – essentially, a flat-backed lute, with a sound more like a modern banjo – which had regained popularity after centuries of disuse, and become one of the most popular musical instruments of the mid-17th century. It was also the one most frequently painted by Vermeer.

Sheet music detail

This painting is interesting, too, because of the “music” on the crumpled sheet of paper lying on the right foreground chair. If you look closely, it doesn’t make musical sense! Further proof that music was used by Vermeer for artistic, rather than for practical, purposes.

A Lady Seated at a Virginal, c. 1670–1675. National Gallery, London.

Lady Seated at a Virginal (and its companion piece, Lady Standing at a Virginal) was a late painting, and it also suggests that “other” anticipated person outside the painting in the form of the viola da gamba with the bow placed (rather impractically) in between the strings. The lady is playing a specific type of keyboard instrument, a muselar virginal, with the keyboard to the right, so in this particular Vermeer has been accurate, and the sheet music looks more feasible. The virginal itself is a work of art, with the pastoral landscape on the lid, and the detailed marbling on the casement and legs. It’s a wonderful moment of arrested playing, as the lady looks out at us – or Vermeer. Again, a reproduction can’t do justice to the jewel-like colors.

Art as music, and music in art. Both are forms that communicate powerfully in a nonverbal way. Looking at their interaction – and it goes both ways, of course – has made me think about each art form with a sharper perspective and, consequently, a deeper appreciation. It’s like suddenly hearing that oboe line that has always been there, but is brought to life in a different performance.

6 Responses to Music in Art