Emerging Romanticism

Romanticism is one of those useful umbrella terms that covers not only our personal predilections – candle lit dinners, happy endings – but also that great swath of artistic endeavor that embraced thinking, literature, art, and music from the late 18th century through the early 20th century. The first whispers of Romanticism came with the Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) movement, which emphasized individual subjectivity and emotion – as opposed to the rationalism of Classicism during the Enlightenment. Even sunny Josef Haydn had a Sturm und Drang period, with his minor key Symphony No. 45, the “Farewell” symphony, being the most famous example.

The first composer to be labeled “Romantic” was the Frenchman, Étienne Nicolas Méhul, who was an important opera composer in France during the Revolution. But it was German poetry, drama, legend, and love of transcendental that put German-speaking countries at the heart of early Romanticism – and the crossover in music happens with Ludwig von Beethoven.

In Beethoven’s early period you can already hear that he was striving for a different impression from Mozart and Haydn. There is an assertive, even aggressive, quality that is famously present in, for instance, his Pathétique Sonata, No 8. The 1802 Heiligenstadt Testament that Beethoven wrote to his two brothers ushers in his “heroic” second period. Heartbreakingly, he writes,

“But what a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone standing next to me heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me almost to despair; a little more of that and I would have ended my life – it was only my art that held me back.”

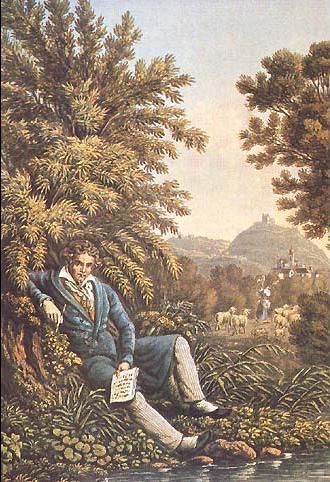

Beethoven composing the sixth symphony, as depicted in the Almanac of the Music Society, 1834

In fact, his art did more than hold him back; it drove him forward into Romanticism, and what followed were epic works: the Eroica Symphony; ‘fate knocking at the door’ in the distinctive opening of his Symphony No 5; the programmatic Pastoral Symphony; his rescue opera, Fidelio; a succession of powerful piano sonatas, including the one that Beethoven considered the greatest from this period, the Appassionata.

By his late period, Beethoven’s Romanticism had full reign in works like his Hammerklavier piano sonata, his late string quartets (including the Große Fuge), and his 9th symphony, with the monumental final movement inspired by Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy.

What Beethoven began in terms of using music to evoke feeling, Franz Schubert crystallized in his 600 lieder. Now, it was more than a setting of a poem to music, but a musical distillation of the emotion embodied in that poem. Think of the yearning vocal line that runs over the rhythmic cycle of the spinning wheel as Gretchen tries to come to terms with her feelings for Faust in Gretchen at the Spinning-Wheel, inspired by Goethe’s Faust. Or, the triplet figures mimicking hoof beats played by the pianist throughout The Erl-King (also after Goethe), beneath the vocal lines of the narrator, the terrified son, the placating father, and the menacing Erl-King. Even without a translation, you can sense the urgency of the text.

The first truly Romantic composer of opera was Carl Maria von Weber, and the American music critic and author, Gustav Kobbé, describes the famous scene in the Wolf’s Glen from his 1821 opera, Der Freischütz, as “the most expressive rendering of the gruesome that is to be found in a musical score.” Weber was amongst the first to make use of the leitmotif – a recurring musical phrase associated with a person or emotion – which would become so integral to Wagner’s operas.

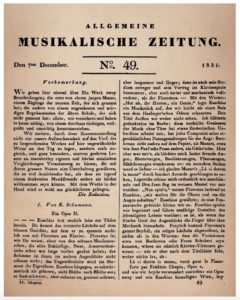

An Opus II.

By R. Schumann

Translation:

David Wärn – Piano Street, 2010

Copyright © 2010 – Op 111 Productions

If a single composer had to be chosen to represent Romanticism, Robert Schumann would have to be a strong contender. His father was a bookseller, publisher, and writer, and literature pervades Schumann’s creativity. While in his 20s, he founded The New Journal for Music and was its editor and influential music critic. In his composing, he was inspired by contemporary writers like E.T.A Hoffmann; his piano cycle Kreisleriana was based on the moody, anti-social composer, Johannes Kreisler – a character created by Hoffman, and an alter ego for Schumann.

With the words “Hats off, gentlemen, a genius,” Schumann introduced Frédéric Chopin in The New Journal for Music. In response to La ci darem la mano, variations for the piano by Frédéric Chopin, Opus 2, the reviewer exclaims in wonder:

“An Opus two!” … and … “Well, that’s something decent at last – Chopin – never heard of him – who can he be? – anyway – a genius!”

Chopin, “the poet of the piano,” was one of music’s early superstars. Even if weren’t for his music – the polonaises and mazurkas, the ballades and scherzi, the etudes and preludes – he would have been a leading symbol of the Romantic era in the public consciousness, in light of his love affair with Georges Sands and his early death.

Another musical superstar of the Romantic era was, of course, Franz Liszt, who pioneered playing the piano in profile at his concerts so that the audience could get the full benefit of his dramatic charisma as a performer. As a composer, aside from the piano transcriptions he made of everything from Schubert waltzes to operas, his enormous contribution to the Romantic movement was the symphonic poem; program music inspired by a poem, play, novel, painting, or work of nature. From Les préludes (d’après Lamartine) after an ode from the first collection of poetry by the French nobleman, Alphonse de Lamartine, to his final symphonic poem, From the Cradle to the Grave, Liszt was using music as a means to conjure up scenes and emotions. It was a concept used to extraordinary effect by Peter Illych Tchaikovsky in fantasy overtures like his famous Romeo and Juliet; Antonin Dvořák in his five late symphonic poems; and Richard Strauss in his cycle of ten tone poems that ranged from Don Juan after an unfinished play by Nikolaus Lenau, to Also sprach Zarathustra after Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophical novel.

A concert of cannons and Berlioz by French caricaturist Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard

Just when you think you have conjured up the quintessential Romantic, another presents himself as an even more viable contender. The life and music of Frenchman, Hector Berlioz, embody the sense of drama, the fascination with the supernatural, the emotionality, imagination, and originality that were the hallmarks of Romanticism. This finds its most articulate – not to say voluble – expression in his Symphonie Fantastique, which tells the story of an artist gifted with a lively imagination who has poisoned himself with opium in the depths of despair because of hopeless, unrequited love – in Berlioz’s case, the Shakespearean actress, Harriet Smithson. The symphony is a wildly inventive, turbulent, truly fantastic work.

And then there’s Richard Wagner, where the cross-pollination of the arts in Romanticism finds its ultimate expression with his concept of Gesamtkunstwerk – total art work; music, words, scenery, and stage movement coming together in a single whole. Wagner wrote the libretto and music for his epic four-part Ring of the Nibelung over the course of about twenty-six years, drawing on elements of German and Scandinavian myths and folk tales, and it still stands as an apex of the Romantic spirit.

This is not to say that Wagner didn’t have his detractors. The “War of the Romantics” was fiercely waged between the camp of Wagner on the one hand, and Johannes Brahms on the other. The Brahms camp was Conservative; they believed that Beethoven was unsurpassable, and they were adherents of traditional musical form, and of absolute (as opposed to programmatic) music. The Wagner camp was Progressive; they also revered Beethoven, but regarded him as a new beginning. They believed in program music and new musical forms. Still, both composers were really different sides of the Romantic coin. Brahms may have been a staunch believer in Classical form, but works like Ein deutsches Requiem and his four-movement 2nd Piano Concerto, coming in at around 50 minutes long, are as clearly products of the Romantic era as Liszt’s symphonic poems.

Isle of the Dead by the Swiss Symbolist Arnold Böcklin

As we slip into the 20th century, late Romantics like Sergei Rachmaninov with his intensely evocative symphonic poem, Isle of the Dead, inspired by a black-and-white photograph of the painting by the Swiss Symbolist Arnold Böcklin; Gustav Mahler with his cycles of lieder interwoven thematically with his nine symphonies; Richard Strauss with his tone poems and his range of operas, continued the spirit of Romanticism. Even Arnold Schönberg, in his first important work, Transfigured Night, was expanding the Romantic idioms of Brahms and Wagner.

It was during the summer of 1908 that Schönberg wrote his first composition without any reference at all to a key. Although music continued to be composed in the Romantic idiom well into the 20th century, this 1908 work by Schönberg marked the emergence of a new era of experimentation in atonality – an experiment that would span the next three generations – even as it marked the waning of Romanticism. Happily, though, we can still be vicarious Romantics every time we lose ourselves in a performance of a work by any one of these emotional, imaginative, and original masters who were composing in the thrall of the Romantic movement.

This essay was based, in part, on a two-part lecture for Odyssey at Johns Hopkins University, Spring 2017

4 Responses to Emerging Romanticism