Top 5 – Halloween Movies (Part 1)

Since Halloween is near, I thought I would share with you my top five favorite horror movies. We certainly have come a long way since I was a child in terms of what is permissable for public viewing. The other day I saw the rotting corpse of a zombie from The Walking Dead on the front page of the Baltimore Sun TV section. When I was a young child, something as tame as the wicked queen from Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs gave me nightmares for years. At age six, walking down the Halloween costume aisle of the present day Rite Aid would have sent me screaming from the store. Of course, a few years later, around the age of nine or so, I could not get enough of horror movies, usually of the low budget Ed Wood variety, since those were about the only ones shown on television at the time. Oh what I would have given to see the original Boris Karloff/James Whale Frankenstein back then.

As I commented in my previous blog “Top 5 -Not”, “once I make up my mind, I don’t have five things but twenty”, and so it was the case here. But let me share with you the first five that came to mind:

1) I Walked With a Zombie, 1943, directed by Jacques Tourneur, produced by Val Lewton, starring Frances Dee, Tom Conway, and James Ellison

Never did a more lurid title grace such an elegant film, and even that is part of its charm. This tale of voodoo, sexual jealousy, and a present haunted by the past on the Caribbean island of St. Sebastian is amazingly based on the book Jane Eyre.

Val Lewton is one of the only acknowledged film auteurs who was not a director but a producer. In the 1940’s, RKO assigned him to produce a series of low budget B horror movies, all clocking in at less than eighty minutes. The studio expected escapist cheap thrills, but instead they got literate, psychologically complex tales of the supernatural, photographed with stunning chiariscuro of shadow and light, with one foot in modernism and the other foot in the nineteenth century English novel.

Val Lewton is one of the only acknowledged film auteurs who was not a director but a producer. In the 1940’s, RKO assigned him to produce a series of low budget B horror movies, all clocking in at less than eighty minutes. The studio expected escapist cheap thrills, but instead they got literate, psychologically complex tales of the supernatural, photographed with stunning chiariscuro of shadow and light, with one foot in modernism and the other foot in the nineteenth century English novel.

As in most Val Lewton films, the central character is a woman (and an intelligent and independent woman at that). Lewton researched the voodoo scenes very carefully, and having seen an actual voodoo ceremony years ago at the Smithsonian Institution I can attest to their accuracy (although they are depicted with such dignity that they practically resemble a Sunday church picnic, and I mean this as a compliment). Lewton is also admired today for his avoidance of racial stereotypes in his Afro-Caribbean characters (only the creepy zombie Carrefour, played by a former basketball player, is anything resembling a “type”, yet even he is ultimately poignant). And he always leaves open the possibility that the horror is in everyone’s minds, almost never actually showing a monster or a ghost but leaving them to our imaginations.

In one of my favorite scenes, the calypso singer Sir Lancelot is entertaining customers at an outdoor cafe with a song about a local love triangle, when he is informed that the sugar planter described in the song is sitting at a table with the pretty young nurse who has come to care for his brother’s comatose wife. He apologizes profusing, swearing “I don’t know who wrote such a song.” But later after dark, when the sugar planter is too drunk and unconscious to notice, Sir Lancelot emerges out of the shadows with his guitar like a Greek chorus to sing one final verse to the listening nurse: “The brothers are lonely, and the nurse is young, and now you have seen that my song is sung.” For me, it is one of the most haunting scenes in the history of film.

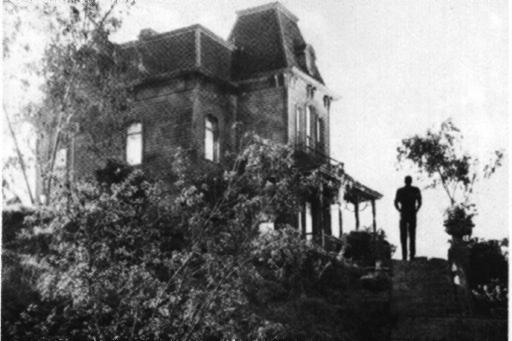

2) Psycho, 1960, directed by Alfred Hitchcock, starring Janet Leigh, Anthony Perkins, and Vera Miles

One of the films that upped the quotient of graphic violence and gore in popular culture to this day, Psycho is a true cinematic masterpiece. Indeed, one of the great works of art of the twentieth century in any form. It is pleasing to be able to say this and know how many cultural mavens will agree. When I was a child, Alfred Hitchcock was known as “the master of suspense” (a not inaccurate description that one may hear at times even today), crafting brilliant escapist thrillers for a mass audience. Then the French got hold of him, particularly Francois Truffaut and Claude Chabrol and their fellow film critics, soon to be directors themselves, at Cahiers du Cinema, the French magazine of analytical film discussion. They declared Hitchcock to be not merely a highly talented entertainer but a great artist, deserving a place alongside James Joyce, Picasso, Stravinsky, and other twentieth century masters.

Claude Chabrol and their fellow film critics, soon to be directors themselves, at Cahiers du Cinema, the French magazine of analytical film discussion. They declared Hitchcock to be not merely a highly talented entertainer but a great artist, deserving a place alongside James Joyce, Picasso, Stravinsky, and other twentieth century masters.

The idea has taken hold to such an extent that I can barely mention Hitchcock’s name these days without being greeted by reverential responses such as “great artist” or “profound psychological insights”. I could not agree more. Years ago I attended a screening of the silent version of Alfred Hitchcock’s early film Blackmail at the Maryland Film Festival. In discussion with some audience members afterwards, someone asked why Hitchcock began the film with a cops and robbers chase that had nothing to do with the story. I ventured the idea that he wanted to grab the audience’s attention in the opening moments with an action sequence. A young man politely disagreed, saying that Hitchcock was too great an artist to use such a crass device. With what I hope was equal politeness, I gave him examples of many revered artists who were not beyond catering to their intended audience from time to time. (The rigourous and cerebral Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu, for example, made sure the labels of whisky bottles faced the camera because a liquor company had donated them to him.) For me it makes them even more loveable. After all, why can’t an artist be both genius and crowd pleaser?

At any rate, Psycho is both. Janet Leigh’s half hour car ride at the beginning of the movie, in which every banal and inconsequential event is somehow frightening, must be one of the most brilliantly sustained sequences any director has ever created. Not to mention the legendary shower scene, studied in film classes to this day. As for pleasing its audience, a film scholar once told me that when United Artists re-released Psycho a few years after its premiere, it became the highest grossing black and white film since The Birth of a Nation. And to quote one of my TV viewing college dorm mates, upon seeing Vera Miles’ climactic confrontation with Norman Bates’ mother, “Cooool!”

3) Kwaidan, 1964, Japan, directed by Masaki Kobayashi, starring Renaro Minkuni, Michiyo Aratama, Keiko Kishi, Tatsuya Nakadai, Katsuo Nakamura, Takashi Shimura, and Kei Sato

Masaki Kobayashi was known as a humanist filmmaker, denouncing the abuses of feudalism, in both contemporary stories such as The Human Condition and period pieces like Hara Kiri. But his most popular film is an exquisite anthology of four unrelated ghost stories with no particular socially conscious theme, featuring major Japanese film stars, filmed in wide screen with some of the most beautiful technicolor images ever seen. The four stories are ironically not Japanese at all, but based on stories by the late nineteenth century author Lafcaido Hearn, born in Greece of British and Greek parentage, who lived for many years in Japan, and drew upon several Japanese folk stories for his adaptations.

The first story, “The Black Hair” tells of a samurai during the middle ages who leaves his beautiful devoted wife to marry for money, but lives to regret his selfishness. The second story, “The Woman in the Snow”, concerns a handsome young man who encounters a female vampire during a deadly storm in an icy wilderness (remarkably, this haunting tale was cut from the original  American release version, but has since been restored). The third and longest story, “Hoichi the Earless” relates the experiences of a blind Buddhist monk whose playing of the biwa (Japanese short necked lute) and eloquent narrative singing inadvertently calls up the spirits of a long deceased clan slaughtered in a famous naval battle (depicted in graphic detail in the opening minutes of the segment). And the final story, “In a Cup of Tea”, is what a friend of mine called the “most post-modern” of the four. A writer sees the face of a samurai in a cup of tea and “swallows his soul”. (If I had to cut one of the stories, it would be this, but it makes for a nice, offbeat ending, after its three more dramatic predecessors.)

American release version, but has since been restored). The third and longest story, “Hoichi the Earless” relates the experiences of a blind Buddhist monk whose playing of the biwa (Japanese short necked lute) and eloquent narrative singing inadvertently calls up the spirits of a long deceased clan slaughtered in a famous naval battle (depicted in graphic detail in the opening minutes of the segment). And the final story, “In a Cup of Tea”, is what a friend of mine called the “most post-modern” of the four. A writer sees the face of a samurai in a cup of tea and “swallows his soul”. (If I had to cut one of the stories, it would be this, but it makes for a nice, offbeat ending, after its three more dramatic predecessors.)

The film contains many horrifying and graphic images, so be forewarned, yet it is an undeniable art film, with the stately pace of the best Japanese films from the 50’s and 60’s, and lengthy periods of suspenseful buildup whose screen time far exceeds the horror. In 1960’s it must have seemed quite gruesome, but younger viewers accustomed to modern horror movies may not find the film too gory but not gory enough. And if you are one of those who constantly complains on the Internet Movie Data Base postings about movies that are too slow, stay away from this one. For those like myself, it induces a pleasing trancelike state with its immersion in pure sensual beauty, making the scares all the more terrifying when they come.

With the exception of a few brief scenes obviously filmed out of doors, Kobayashi filmed Kwaidan in an airplane hanger so he could stylize the settings. Horizons at sunset are deliciously artificial in their lurid colors. In one story, large painted eyes appear periodically in the sky. The music is by Toru Takemitsu, a famed Japanese classical composer, who uses traditional Japanese percussion instruments to create eerie sound effects in a truly experimental score. The opening credits alone are a tour de force, resembling a lava lamp, like different colored inks dispersing through water, but processed on a white background.

Kwaidan won the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Film. Japanese horror movies have been undergoing a Renaissance in recent years, but none of them are as sumptuous as this one.

To be continued …

Tags:Halloween, movies, top5

One Response to Top 5 – Halloween Movies (Part 1)