World Classical Music

by Reed Hessler

by Reed Hessler

This article originally appeared in the WBJC program guide in January 2009. It has been revised only slightly.

When I was growing up in the 1950’s and 1960’s, classical music was just that. There was classical music, and then there was everything else. Today, when the term is used in the context of other music, it is often referred to as “European classical music”. Particularly German musicians, and to a great extent Italian and French, are responsible for creating the template which set this astounding human creation in motion.

In the nineteenth century, nationalist fervor swept Europe, and it was not long before nationalism became a major influence in classical music. Czech composer Bedrich Smetana was a political activist, and the popularity of his nationalist opera, The Bartered Bride inspired the young Antonin Dvorak to compose his Slavonic Dances and incorporate the style of Czech folk song and dance into his symphonic and chamber works, that were initially patterned after the German models. When German composers abandoned writing symphonies, following the lead of Wagner who asserted that opera was the new symphonic music, Russian composers picked up the standard, and composed the most popular symphonic music between Schumann and Brahms. Foremost among them was the group that came to be known as “the Mighty Handful”: Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, Mussorgsky, Bakakirev, and Cui. They not only composed music in a recognizably Russian style, but wrote on the importance of nationalism in Russian music. (Although Tchaikovsky was not considered to be a member of the group, from the present day perspective, his greatness and “Russian-ness”can never be in doubt.) Before the end of the twentieth century, almost every country in the world would find a way to put its national stamp on “classical music.

In his Symphony No. 9 “From the New World”, Dvorak moved from nationalism to pan-nationalism, by showing people from a country not his own how their own music should sound. It must have been a first: Dvorak showing us that the truest nationalist would inevitably transform into an internationalist.

I had a college professor in the 1970’s who thought so-called “nationalist” styles were a hoax. He was quite modest and good natured about presenting his opinion that all classical music was in the style of the German masters, and became “national” only by inserting a folk tune here and there. While there is some truth to this observation, I would submit that the true measure of any music’s worth is simply how good it is. Dvorak’s Symphony No. 9 “From the New World”, for example, is to my mind a masterpiece. Who cares if it is not as harmonically innovative as Wagner, or as contrapuntally complex as Bach? Over a century after its premiere, the work still has the power to engage and compel an audience for the three quarters of an hour that they are in its presence. There is nothing trite or simple-minded about the musical means through which it achieves this. Indeed, it is a remarkably original work, unlike anything else Dvorak ever composed. Or take, for another example, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade. I would also contend that this much imitated orchestral tour de force is not simply clever, pseudo-Middle Eastern schlock, but also a masterpiece. Its orchestration alone is some of the greatest in history, but its musical storytelling is what draws us in..Thousands of people have composed symphonies in the past two hundred years. None of them lacked for seriousness of purpose or depth of musical education. Only a few, however, had the ineffable element of talent (dare I say genius?) to create a work as popular as Scheherazade.

The heroes of musical nationalism in the past century are too numerous to mention in a brief article, but first and foremost would come Bela Bartok. While Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies and Brahms Hungarian Dances were not completely devoid of authentic folk influences, it was Bartok who (along with his colleague Zoltan Kodaly) traipsed through the hinterlands of Eastern Europe, recorded actual folk songs and dances with the new invention, the phonograph, and then analyzed and codified them with the academic tools of musical analysis, thus creating the field of ethnomusicology, and giving the imprimatur of academic respectability to music that was not created by conservatory trained composers. It was only a simple step from this to incorporating these styles into the work of a conservatory trained composer such as Bartok.

Manuel de Falla once complained that no one outside of his native Spain took him seriously when he wrote music that did not “sound Spanish”, and yet few composers have written “Spanish sounding” classical music with such flair and originality as de Falla. Works like The Three-Cornered Hat and Nights in the Gardens of Spain go without saying, but even in his more astringent, neo-Classical Harpsichord Concerto, a personal favorite, the presence of Spanish rhythms and melodic turns of phrase is inescapable. It is a work which Igor Stravinsky would have been proud to write, if only he had been Spanish.

That said, is it necessary for a composer to “sound national” to be a great national composer? Or is it enough to simply be a great composer? Finland’s Jean Sibelius comes to mind. He undoubtably secured his nationalist credentials by composing Finlandia, and also by basing many of his works on Finnish and Scandinavian folk tales and legends. Furthermore, even having never visited Finland, I find his music evokes the country (or at least some Scandinavian country). It quietness is eerie, immediately transporting me to an icy fiord. The music is full of empty spaces, drawn out musical phrases, spare orchestral textures, and lengthy pauses, suggesting a long night in the frozen north. But is this the style of Finland, or simply the style of Sibelius? He is, for me, one of the most original composers of the twentieth century, and I do not wish to pigeonhole him by saying he sounds “like Finland”, when indeed he sounds like no one else. Aaron Copland, a quintessential American composer, also wrote “spacious” music, and it reminds us of the Great Plains and the Appalachian Mountains. Could knowing that Copland is American, and knowing that Sibelius is Finnish, influence the way we hear their music? (Although I will grant that no one would ever mistake “Hoe Down” for Scandinavian music.) Ultimately, I would have to say that both answers are correct. Sibelius and Copland, to my mind, are great enough to be both national and individual at the same time.

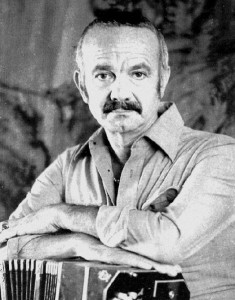

Astor Piazzolla, the late Argentine tango composer, took the opposite approach of Bartok when fusing his national dance style with classical music. Unlike Bartok, who used folk dances as source material for his modern classical compositions, Piazzola was a star tango performer who expanded the harmonic, rhythmic, and structural constraints of the popular tango style. Although brought up with the music of Bach, Piazzolla knew by the age of thirteen that he wanted to play in a tango band. But like George Gershwin, he longed to cross over from popular to classical music. He studied for a time with Brazil’s Albertro Ginastera, himself a composer who incorporated national dance styles into classical music.

Finally in the 1950’s, in his early thirties, Piazzolla traveled to Paris, where he studied with the legendary composition teacher Nadia Boulanger, who had numbered among here illustrious pupils Aaron Copland. Looking at the music he had composed up that point, Boulanger commented, “This is Bartok. That is Ravel. But what I want to hear is Piazzolla. What do you play which is yours?” He recalled how embarrassed he was to admit that he was a tango musician who played the bandoneon, an accordion-like instrument, in cabarets. Boulanger persisted, demanding that he play the bandoneon for her. When he was finished, she declared, “That is it. That music is Piazzolla..” After his meeting with Boulanger, Piazzolla destroyed all his earlier compositions, and set about creating what came to be known as the Nuevo Tango, a truly innovative new tango style.

Piazzolla’s Nuevo Tango has been described as a highly unique blend of jazz, the Baroque passacaglia (variations on a repetitive bass line), contemporary harmonies, and the Argentine tango. Traditional tango musicians were outraged at what seemed to them to be a repudiation of the great tango tradition, but Piazzola found a new audience among political radicals and, eventually, young classical musicians. I must admit, I was initially on the fence about Piazzola’s music, finding it interesting but suspecting it was little more than a clever, quirky fad. But time has proven me wrong. Twenty-three years have passed since Piazzola’s death in 1992, and today his music is more popular and frequently performed than ever. As with much music throughout my life, Piazzola has grown on me over the years. His music lurches from wistfulness to a strange urgency, as if revealing the composer’s deepest spiritual turbulence, and at all times it retains the feeling of the tango.

The musical traditions of the Middle East and Asia might seem the antithesis of the European classical style; a profound, complex classicism that occupies a world of its own, with modal and pentatonic scales, micro-tone inflections, linear, repetitive rhythmic development, and coloristic inflections abrasive to many Western ears. Nonetheless, Asia now has some of the largest audiences for European classical music in the world. Yo Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble, deftly blending modern classical composition with traditional Middle Eastern and Asian music, recorded and toured for over a decade..

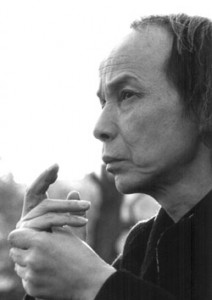

The late Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu grew up hating his country’s traditional music, which he associated with the Japanese nationalism responsible for World War II. But he could not completely avoid the influence of his musical forbears. At certain points he discovered inadvertent Japanese musical influences in his earlier compositions, and immediately destroyed them. He was drawn to the French composers Debussy and Messiaen, who ironically had been influenced by traditional Japanese music themselves. Eventually he made common cause with the avant garde, particularly the aleatoric or “chance” music of John Cage. But ultimately Takemitsu admitted that he could not resist the allure of Japanese Bunraku puppet theater music which he found mesmerizing. Indeed, Takemitsu began to realize Japanese classical music and the avant garde had many elements in common, such as their emphasis on long silences, and sound created for its own sake, with no regard to melody or structure. Japanese instruments such as the shakuhachi flute and the stringed biwa began to appear in his compositions, not merely creating exotic interludes in otherwise European-styled concert music, but transforming its sound completely. Finding his unique voice, Takemitsu became the most internationally acclaimed of all Japanese composers..

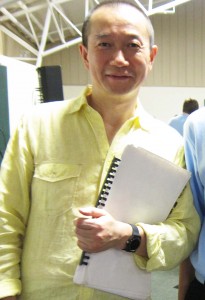

In an era when contemporary operas are lucky to receive a single performance, Chinese composer Tan Dun’s popularity brought him commissions for four operas and an oratorio. His opera The First Emperor was one of the few contemporary operas performed at the Metropolitan Opera in decades, and featured tenor Placido Domingo, in his first ever performance in a world premiere at the Met. Add to this an Oscar for his score to the film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and the major presence of his music in the 2008 Summer Olympics, and Tan Dun can truly claim to be one of the world’s most prominent composers..

In 1959, Chen Gang and He Zhanhao were students at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. They composed a violin concerto inspired by the popular Chinese tragic romance of the Butterfly Lovers, incorporating some traditional Chinese musical styles in the solo violin music, such as the bending of pitches, and adding Chinese percussion instruments to the orchestra, occasionally echoing the popular melodies and rhythms of the Chinese opera. The work was suppressed during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960’s, but in the subsequent decades it has become one of the most frequently performed works by a Chinese composer, not only in China, but around the world. It even received a performance in Baltimore a few years ago. First recorded in two separate versions by violinist Takako Nishizaki, it has recently been recorded by violinist Gil Shaham. In many ways, the concerto seems conservative and conventional, with exotic elements that resemble European versions of Asian music as much as traditional Asian music, but I find it irresistible. Perhaps if we can get over being purists, an entertaining work like the Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto might find its way into the repertoire, drawing more people into the concert halls, and continuing European classical music’s centuries old evolution into a truly international art form.