“Music is Life”

2014 marks the 100th anniversary of the start of what H.G. Wells referred to as “the war that will end war.” We now know that David Lloyd George was the one who got it right when he said, “this war, like the next war, is a war to end war.” Still, during The Great War, as in every war, and just as today in places like Syria and Sudan and Afghanistan, people managed to carry on with their lives somehow, and a vivid example of this is a sampling of the extraordinary works that were composed a century ago as that devastating trench war got underway.

Most remarkable were the works composed in Germany, given that it was the fulcrum of World War I. In 1914, Alban Berg began work on his tortured opera, Wozzeck – a brutal and uncompromising piece based on an unfinished play by Georg Büchner. As a disciple of Arnold Schönberg, Berg wrote one of the first atonal operas, bending and even breaking every operatic rule. One certainly doesn’t walk out of Wozzeck humming the tunes. And it’s not just that he didn’t use tonality, but that he used musical forms more typically associated with instrumental music. So, the first act is made up of a Suite, a Rhapsody and Hunting Song, a March and Lullaby, a Passacaglia, and a Rondo. In the second act there’s a Sonata-Allegro, a Fantasia and Fugue on 3 Themes, a Largo, a Scherzo, and a Rondo, and the third act is a series of five Inventions based on themes, notes and rhythms.

Berg’s work on the opera was interrupted by his army duty during the war (he used soldiers’ barracks as the background for some of the scenes) and he didn’t complete it finally until 1922. But, after it was first produced in 1925, it became phenomenally successful – so much so that he could live comfortably off the royalties – until the Nazis labeled it “decadent art” in 1933. In its theme of fatally jealous love it was no worse than many operas (Pagliacci springs to mind) but it was the musical treatment that was outrageously shocking. It has to be said, though, that the unfettered forms of atonality are remarkably effective in conjuring up the alienation, violence, madness and the thought processes of the characters, culminating in Wozzeck’s search in the pond for the lethal dagger before he drowns, calling out, “ich wascher mich mit Blut–das Wasser is Blut … Blut” (I wash myself with blood–the water is blood … blood). Not such cheerful stuff.

Berg’s work on the opera was interrupted by his army duty during the war (he used soldiers’ barracks as the background for some of the scenes) and he didn’t complete it finally until 1922. But, after it was first produced in 1925, it became phenomenally successful – so much so that he could live comfortably off the royalties – until the Nazis labeled it “decadent art” in 1933. In its theme of fatally jealous love it was no worse than many operas (Pagliacci springs to mind) but it was the musical treatment that was outrageously shocking. It has to be said, though, that the unfettered forms of atonality are remarkably effective in conjuring up the alienation, violence, madness and the thought processes of the characters, culminating in Wozzeck’s search in the pond for the lethal dagger before he drowns, calling out, “ich wascher mich mit Blut–das Wasser is Blut … Blut” (I wash myself with blood–the water is blood … blood). Not such cheerful stuff.

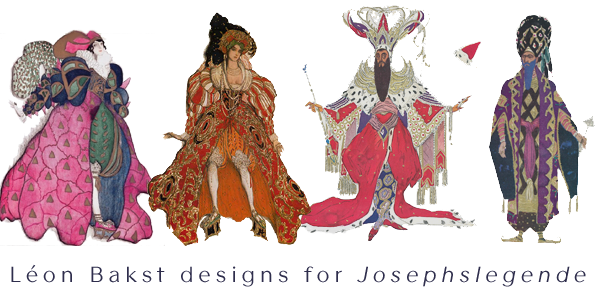

The Great War was clearly a watershed not only in terms of world history but also in world culture. Amongst the last works that harkened back to the Romanticism of the 19th century was Richard Strauss’s ballet Josephslegende. It was sandwiched between his operas, Ariadne Auf Naxos and Die Frau ohne Schatten and he wrote it for the Ballets Russes at the suggestion of his long time librettists, Hugo von Hoffmansthal. He conducted the glittering premiere at the Paris Opera on May 14th 1914, and it also played to sold-out performances in London under the baton of Sir Thomas Beecham. With the outbreak of war three months later, though, the ballet slipped into obscurity, and Strauss never received his 6000 gold francs conducting fee from Diaghilev.

The war was not the only reason that the ballet didn’t maintain a foothold in the repertoire; one of the main reasons is that it calls for tremendous orchestral forces, foreshadowing Die Frau ohne Schatten. Strauss was not a religious man and he found the central, God-seeking figure of Joseph uninspiring. After all, Strauss was the composer who had given us Salome and Elektra, and he was much more interested in writing music for exotic scenes, like the attempted seduction of Joseph by Potiphar’s wife. As if to make up for his lack of enthusiasm for the protagonist of his ballet, Strauss wrote a lavish score that called for six horns, four trumpets, four trombones, quadruple woodwind, a threefold division of violins, harps, celestas, piano and organ. It’s simply too daunting for your regular ballet orchestra. An interesting postscript to the history of the ballet is that following the next great war – World War Two – Strauss rescued this work from obscurity and made a Symphonic Fragment for reduced orchestra, which is also well worth hearing.

While the Germans were occupied with their side of The Great War, Gustav Holst in England began sketching Mars, The Bringer of War, the first of the seven tone poems that make up The Planets. His idea behind a composition around the seven planets – Mars, Venus, Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – was astrological (the effect that the planets have on human personality) rather than astronomical (the scientific study of celestial objects). There is some speculation about whether or not Holst wrote Mars as a response to the outbreak of the war but, in any event, the music is strident and urgent, conjuring up the horror and stupidity of war.

Holst originally wrote the series as a piano duet but, with the evident inspiration of Post-Romantic contemporaries like Richard Strauss, Wagner, Glazunov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Stravinsky, and even early Schönberg, he scored it for a massive orchestra that Strauss would have been proud of: four flutes, three oboes, English horn, three clarinets, three bassoons and contrabassoon, six horns, four trumpets, three trombones, two tubas, a huge percussion section (including six timpani and tubular bells), two harps, strings and two women’s choruses. Holst worked on the piece throughout the war, and Adrian Boult conducted the premiere before an invited audience of about 250 people on September 29th, 1918, shortly before the armistice.

Holst originally wrote the series as a piano duet but, with the evident inspiration of Post-Romantic contemporaries like Richard Strauss, Wagner, Glazunov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Stravinsky, and even early Schönberg, he scored it for a massive orchestra that Strauss would have been proud of: four flutes, three oboes, English horn, three clarinets, three bassoons and contrabassoon, six horns, four trumpets, three trombones, two tubas, a huge percussion section (including six timpani and tubular bells), two harps, strings and two women’s choruses. Holst worked on the piece throughout the war, and Adrian Boult conducted the premiere before an invited audience of about 250 people on September 29th, 1918, shortly before the armistice.

On the other side of the Balkans, the Russians, led by their tsar Nicholas II, entered the war with gusto in defense of the Serbs. Within a year, the impact of the war had begun to demoralize the empire, and before the war’s end, the tsar had abdicated. In that same time frame, Igor Stravinsky completed the first stage of his ballet, Les Noces (The Wedding). He started sketching it in 1914, and by 1917 he had completed the piano score. He took another four years to settle on the instrumentation, and in that process he began the evolution from his Russian period to Neo-Classicism. At first, he toyed with a huge orchestra (a la Strauss and Holst), then he considered a divided orchestra (one of which would have been an onstage folk orchestra). He even contemplated a mechanical orchestra (including self-playing pianolas and hammered cimbaloms) before he finally settled on four pianos with a percussion ensemble, along with vocal soloists and chorus. That was an unusual enough combination in itself, turning the piece into a dance cantata, or a ballet with vocalists.

Although this ballet was not a direct response to the war, it was pivotal in its way. It was the culmination of Stravinsky’s Russian period, following on from his three great, early ballets for the Ballets Russes; The Firebird, Petroushka and riotous Rite of Spring. Going forward, he would evolve his style into a more pared down Neo-classicism. Also, the ballet, with the text by Stravinsky and choreography by Bronislava Nijinska, has the whiff of a feminist statement. Through the four scenes – At the Bride’s House, At the Bridegroom’s House, The Bride’s Departure and The Wedding Feast – they trace the storyline of the bride’s anxiety, her commiserations with her bridesmaids, the parents’ sorrow at the loss of their children, and the groom’s anticipation of the wedding night, highlighting the restrictive role of women in the Russian peasant culture and their requirement to marry in order to maintain the community. In retrospect, this transitional ballet is a metaphor for the before and after of The Great War and also the collapse of the Russian empire during the October Revolution, which took place just as Stravinsky was finishing the piano score.

At the start of World War I, Denmark remained neutral. In 1914, the Danish composer, Carl Nielsen, began to plan his Symphony No. 4, calling it The Inextinguishable – “Under this title the composer has endeavored to indicate in one word what music alone is capable of expressing to the full: the elemental Will of Life. Music is Life, and like it is inextinguishable.” The symphony begins with a forceful struggle between the keys of C major and D minor, and it ends with a battle between two sets of tympani, placed as far apart on the stage as possible.

Nielsen worked on this work between 1914-1916. As the war progressed and the Germans terrorized the region, Denmark began to side with the allies, and the conflict of the war is clear in Nielsen’s 4th Symphony. Finally, though, the key of E major triumphs at the end to illustrate his premise that music and life are inextinguishable – if one takes this to mean not the individual life, but the concept of a life force. And one can take that analogy further, to mean that even in war, a war supposed to end all war, somehow life and creativity will find a way to go forward.