“In sweet music is such art …”

by Judith Krummeck

This year, as we celebrate 400 years of William Shakespeare – baptized April 26th 1564, died April 23rd 1616 – it is quite overwhelming to take stock of the enormous and far-reaching legacy he left us. Aside from his almost 40 plays, running the gamut of comedy, tragedy, and history, there are his unforgettable characters, which range from Macbeth to Malvolio. We use, without thinking, the myriad words he invented, from amazement to zany. And then there is the music. It’s not only that his plays have inspired composers over these four centuries (as I wrote about in a piece here four years ago) it’s that the plays themselves resound with music. Shakespeare made more than 500 references to music throughout his works; here are just a few:

In sweet music is such art,

Killing care and grief of heart

– King Henry VIII

It is the lark that sings so out of tune,

Straining harsh discords and unpleasing sharps.

– Romeo and Juliet

If music be the food of love, play on;

– Twelfth Night

How sweet the moonlight sleeps upon this bank!

Here will we sit, and let the sounds of music

Creep in our ears:

– The Merchant of Venice

Even before Shakespeare’s plays gave Elizabethans a taste for theatre, there’d been a long tradition throughout medieval times, and even before, of musical accompaniment to ballads and epic sagas, and the tradition evolved quite naturally into the theatre of the Renaissance. Music underscored the emotions in Shakespeare’s tragedies. The pomp and ceremony in his history plays were conjured up with trumpets and drums. Songs added a deft touch to the lightheartedness of his comedies – as in the hilariously absurd “What dreadful dole is here?” from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, when the mechanicals take off the moralistic laments that were high fashion in the 16th century.

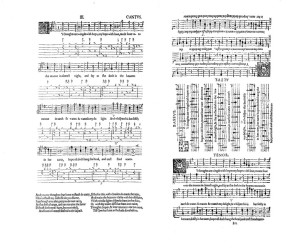

Song for 4 parts and Lute “My thoughts are winged with hopes” from The first booke of songes or ayres by John Dowland

Music was an integral part of Shakespeare’s life. He heard it on the streets of London in the ballads, the street cries, and the love songs. Madrigals, based on light, a cappella models from Italy, were the pop songs of the day. At the Elizabethan court and in the houses of the nobles he frequented, Shakespeare enjoyed the instrumental music and madrigals of composers like John Dowland, whose first book of Ayres in 1597 – the year of The Merchant of Venice – became an instant bestseller. At church, Shakespeare heard contemporary masses by the leading composer of religious music, William Byrd, who was the chief organist and composer for Queen Elizabeth.

Some of Shakespeare’s contemporaries composed settings of songs from his plays – amongst the most famous are Thomas Morley’s “It was a Lover and His Lass,” one of six songs from As You Like It, and Robert Johnson’s settings of two songs by Ariel from The Tempest: “Full Fathom Five” and “Where the Bee Sucks.” Sadly, though, very few of the songs still exist in their contemporary settings, and we can’t be sure that even those that do exist were used in Shakespeare’s own productions. Some of his most beloved lyrics – “Sigh no more, ladies” from Much Ado About Nothing, “Who is Silvia?” from Two Gentlemen of Verona, and “Come away, death” from Twelfth Night – are no longer attached to their melodies. It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly how much of the music in his plays was original to Shakespeare, and how much he was borrowing from popular songs of the time; it seems to be a mix of both. “Come, thou monarch of the vine” from Antony and Cleopatra, for instance, was a generic drinking song of the time. And it’s likely that “Take, O, take those lips away” from Measure for Measure and “O mistress mine” from Twelfth Night also predate the productions of those plays.

The reason that Twelfth Night and The Tempest have six songs apiece is that they were presented at court. Twelfth Night was first performed at Whitehall – literally on Twelfth Night, 1601 – as part of a traditional royal celebration of the holiday. The Tempest was presented at court twice, first in 1611 at Whitehall and again in 1613. For these special occasions, Shakespeare could probably have made use of court singers and instrumentalists. For regular productions at The Globe, though, the musical component was more modest, even though there was generally at least one song in every play. Usually, there was a boy actor who could sing, and sometimes also play an instrument. For the rest, the actors who played servants, clowns, fools, rogues, and minor characters were the ones who would break into song.

The main characters, more often than not, were sung to, rather than singing themselves. But, Shakespeare being Shakespeare, he bent the rules sometimes to create a resounding dramatic effect by having a main character sing. Ophelia sings fragments of folk songs as her mind deteriorates during her mad scene in Hamlet. Edgar pretends to be mad by singing folk songs in King Lear. Desdemona sings the popular 16th century “Willow Song” shortly before Othello murders her. Shakespeare used song to undergird the characterization in other ways too. When Ariel sings “Where the Bee Sucks,” in The Tempest, he is describing himself. To further his evil scheming against Othello, Iago sings drinking songs to encourage Cassio’s drunkenness, so that he can worm his way into his confidence.

As to performance practice, the musicians typically sat in a gallery in the section known as “The Lords’ Rooms” above and behind the stage, where they could watch the action and accompany it accordingly, somewhat in the way of film score. The musicians would sometimes be integrated into the action, to accompany songs on stage or to play the trumpets and drums in ceremonial scenes. They were also placed in strategic places around the theatre to create special effects – like underneath the stage to add to an eerie, ghostly quality for Macbeth.

We can hazard a pretty informed guess about the musical sound and timbre of the Elizabethan era because we still know most of the instruments of that time, or at least their descendants. As in our modern orchestras, there were strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion, with organs, virginals, and harpsichords being the keyboard instruments of the day. Amongst the strings, there was the whole viol family, in addition to the lute, which was the most popular stringed instrument of the Renaissance. In the woodwinds and brass, there were recorders, piffari, shwams, double-reed krumhorns, cornetts, and sackbuts. Of these, piffari were forerunners of the modern flute; the oboe (taking its name from the French, hautbois, meaning high wood) eclipsed the shwam; and sackbuts would eventually evolve into trombones. The percussion was made up of drums of various sizes, and bells were used to great effect too.

Elizabethans believed that the four humors – blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm – led to certain temperaments – sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic. Similarly, they believed that certain instruments had symbolic significance. Usually, Shakespeare’s stage directions (the most priceless of which is, “Exit, pursued by a bear” from A Winter’s Tale) would simply indicate, “Music is played.” Occasionally, though, he would call for specific consorts or instruments. Hoboys, or oboes, were thought to bode ill, and they heralded the banquet scenes in Macbeth and Titus Andronicus, and the play within the play in Hamlet. Viols and lutes, on the other hand, were thought of as benign instruments that could ease melancholy and calm the human spirit, and would surely have been the accompaniment for a song like “Sigh no more, ladies” from Much Ado About Nothing.

William Shakespeare, a product of his time now reaching into ours, would also have had an understanding of Musica Universalis – Music of the Spheres – the Renaissance concept that the celestial bodies of the sun, the moon, and the planets moved in musical proportions, and that heavenly and earthly harmonies had an effect on the human spirit. Even by today’s standards, we can see how profoundly Shakespeare used music in his plays to give depth to a character and build high drama in his plays, how fully he understood that “in sweet music is such art.”

::

References:

The Course Hero® – Elizabethan Era

Internet Shakespeare Editions – Shakespeare and Music

Encyclopædia Britannica – “Music in Shakespeare’s Plays,” by Mary Springfels