Educated and Not-So-Educated Perspectives on New Music

At least one of you has noticed that, contrary to my “mission statement” I posted when I first started working here, I haven’t gotten around to playing a lot of new music on the radio. That’s largely because I remembered that radio is a medium on which you can’t skip past what you don’t like, and unlike a station backed by a steady stream of dollars for educational purposes, we have to think about whether or not people are listening and/or enjoy what’s playing. So I’ll leave that up as a testament to my naïveté. Being out of the game for two years takes a toll!

This is of course not to say that I have lost any of my interest in new music, however, and since this is the internet, where you can skip to the end or skip the thing entirely (though I would enthusiastically recommend against doing so), we’ll be talking about new music, and we’re going to have just an excellent time. We’re going to look at new music through the eyes of active composers and my own far less practiced point of view.

Many of you are likely aware that I did a nearly-monthly podcast last year called Student Composer of the Month, where I would talk with a local or formerly local, usually via academia, composer about pretty much whatever we want. We would generally start with where they came from as a student of music and it would usually spin into discussions of musical philosophy, the state of music in general, and where they see music going in general, with little relation of their own music to what is or is supposed to be happening in music. Tom Hulce’s Mozart from the film Amadeus would be a likely unemployed anomaly today (and is of course at least an exaggeration of the composer himself); you’ll hear no composer refer to their works as “the best music yet written,” and while they have their views on what music is better than others, they’ll never begrudge or scoff at someone for having Mozart as their favorite composer or not understanding new music. A fair amount of it is indeed difficult to grasp and there are some works that might not sound to some people like music at all. Music is now sometimes composed in the classical style for instruments and sounds that are not traditionally found in classical music. That all being said, music is moving back from the hardcore academic and inaccessible music of the mid-20th century, composed as a reaction to the emergence of popular music, into more tonal and accessible realms, though still exploring yet unheard arrangements of sound.

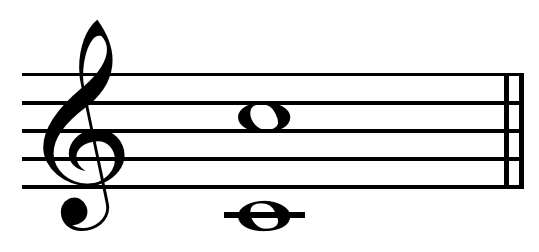

A traditional consonance, the perfect octave.

One word you’ll often hear the composers on my podcast cringe at is “beautiful.” The reason is that the word “beautiful” seems to have a quite narrow definition when it comes to music, and it implies negativity in works whose primary quality is not beauty. Another debated concept is that of consonance; in my undergraduate music history class, I learned about composers in the early twentieth century aiming to use the four “standard dissonant intervals”—that is, seconds, fourths, sevenths, and tritones, as “consonance,” while unisons, thirds, fifths, sixths, and octaves would be seen as “dissonant.” Instead of specifying a definition of “consonance,” today’s composers are expanding the range of sounds that can be heard as “consonant” by contrasting them with an equally wide array of “dissonances.” The rules of what one can do with music are as loose as my explanations of these concepts as they relate to new music—you can create, follow, or break as many of these rules as you’d like, so long as there is a purpose for doing so. Sometimes music is composed for a certain event, or a song set to a certain poem. There are calls for scores that generally ask for shorter works—overtures and the like, intended to provide a sprinkle of new music to accompany orchestras’ larger standard program, which frustrates some composers and new music advocates because while standard repertoire is standard for a reason, it doesn’t make much room for the wide array of composers who don’t have centuries of performance to back up the quality of their music, though the process of composing said music is really not very different from how music has always been composed—the difference is what you’re hearing!

A traditional dissonance, the minor second.

Speaking of what you’re hearing, what I have to provide is perspective as a listener of new music. I am by no means an expert on the subject—just a fan who wants to find out more. As you might know, my broadcasting background is in college radio, where the station’s financial independence afforded its DJs an array of music to play that challenged host and listener alike. Washington Post classical music critic Anne Midgette, in her review of a show I’ve been singing in, related our treatment of standard repertoire (the Verdi Requiem), because of its pairing with a concurrent monologue, to the rawness of when the piece was new, when it was “provocative, unfamiliar, something you might not like.” I’ve always found that unfamiliarity exciting, though I understand, especially in today’s pop-dominated world, that familiarity is one of the main things listeners seek in music these days. The music I would play on the station would take time to acclimate to; it was challenging and sometimes grating, but it was music that I had never heard and wanted to share with listeners, and sometimes they would turn the radio off, but those that stayed got to share in that excitement of discovery. This goes the same for new classical music (which you’ll notice the “grating” link is included in); my interest is that of discovery, of course without ever forgetting what great music came before.

I would like to know, especially from those of you who do not play music yourselves (since most of you likely have a decent amount of experience listening to classical music), what you think of new music. Let’s get a discussion going and then we’ll hear from my old friend. In the meantime, check out these 5-minute clips, many featuring relatively new music, recommended by artists and compiled by the New York Times.

5 Responses to Educated and Not-So-Educated Perspectives on New Music